Abstract

The 2007 global economic crisis and public policies implemented to resolve it have modified the conditions under which enterprises operate, thus having great effects on business tactics and decisions. This paper employs a comparative analysis of the pre- and post-crisis movements of Greek small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to Bulgaria in order to examine the impact of the crisis and the applied public policy on firm-internal relocation factors, such as size, sector and relocation incentive, and the effects of relocation on business performance. Greek SME movements to Bulgaria have recently increased considerably due to the adverse effects of the crisis on the Greek economy. Results demonstrate that, while in the pre-crisis period many Greek businesspeople viewed relocation to Bulgaria as an entrepreneurial opportunity for firm expansion, since 2007 relocation has been perceived as a necessity for the vast majority of Greek entrepreneurs in order to stay in business. However, evidence is provided for a clear division between businesspeople, managing strong, and medium-sized firms and seeking business growth and improved competitiveness, and entrepreneurs who own small, unproductive enterprises and who made efforts to maintain business without seeking quality improvement. Consequently, many of them failed to stay in business since they overlooked internal to firm changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

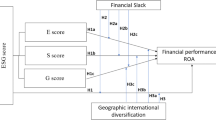

Firm relocation decisions are made within diverse socio-economic frameworks and are affected by factors which are both internal and external to the firm (Brouwer et al. 2004; Labrianidis 2008; Aspelund and Butsko 2010). In economic geography literature, it is widely accepted that operational cost reduction, market expansion and technological improvement constitute the main relocation incentives (Domański 2003; Kiss 2007; Smallbone et al. 2012). In this analysis, firm relocation is usually perceived by businesspeople as an entrepreneurial opportunity for higher profits, although several entrepreneurs move their firms attempting to stay in business in cases of economic recession in specific places and economic sectors (Karagianni and Labrianidis 2001; Zahra and George 2002; Alberti 2006; Wright et al. 2007). In turn, the change of location affects the economic performance of enterprises, with several scholars emphasizing the significance of changes that are both internal and external to the firm to business competitiveness (Krugman 1996; Bristow 2005; Sammarra and Belussi 2006). These insights refer to conditions of economic growth at the macro level, from the late-1970s to late-2000s, when annual global GDP growth was always positive (Castells 1996). However, the 2007 global economic crisis (GEC) has significantly affected the business conditions in many territories. While the impact of the crisis on business growth and firm registration has been examined (Duchin et al. 2010; Claessens et al. 2012; Godart et al. 2012), the changes in business conditions encourage a close assessment of the crisis’ effects on firm relocation, its internal factors, and its drivers.

The research aim of this paper is to examine the impacts of the GEC on firm-internal factors of business mobility and the effects of relocation on business performance. While other studies have examined relocation in two distinct periods of economic growth (Bitzenis 2006; Liao and Chan 2009), this manuscript presents the first-ever study that compares pre- and post-crisis business movements. Therefore, it contributes to the literature of business mobility (van Dijk and Pellenbarg 2000; Domański 2003; Brouwer et al. 2004; Kiss 2007; Wright et al. 2007; Smallbone et al. 2012) by deepening our understanding about the effects of the crisis on firm relocation. Moreover, this paper analyzes the effects of relocation on business performance, by examining the impact of aspects that are both internal and external to the firm. Most studies have examined this impact under conditions of economic growth (Oerlemans et al. 2001; Sammarra and Belussi 2006; Giner et al. 2017). On these grounds, this article seeks to expand our understanding of the complex relationship between firm internal and external factors and its impact on business competitiveness in the context of economic decline.

Particularly, heeding the call of Morkutė and Koster (2016) for using long time series to understand the effects of the GEC on business mobility, this paper seeks to answer three research questions. First, what is the impact of the crisis on the relocated firms in terms of size, location, sector, and re-organized business structure? Second, how does the crisis affect the wider firm relocation incentives? Third, what is the impact of relocation on the performance of firms that have moved?

To achieve the research aims, this paper focuses on Greece. In the geographically uneven impact of the GEC (Wójcik 2009), Greece has been significantly affected, being the only developed national economy since the end of World War II that recorded economic recession for six consecutive years (2008–2013) and losing 25% of its GDP (Eurostat data). The country has been severely affected by the crisis due to its disadvantageous positioning within the global division of labor, its weak productive structure and institutions, and the government austerity policies implemented to resolve the crisis. On these grounds, Greek small- and medium-sized enterprisesFootnote 1 have been adversely affected. On one hand, they are small, credit-dependent, and family firms, and their owners ignore technological upgrade and long-term business strategy (Liargovas 1998; Papagiannakis 2008). On the other hand, they constitute the backbone of the Greek economy as they crucially contribute to employment (87% of private sector employees in 2009) and production (73% of total value added in 2009) (Eurostat). Therefore, Greece could be perceived as an archipelago of micro and small firms, as the 99.9% of all Greek enterprises are of small and medium size.

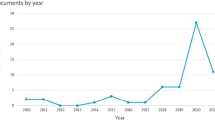

Against the background of great economic decline, thousands of Greek entrepreneurs have moved their firms to Bulgaria since 2007: almost 1000 Greek firms were operating in Bulgaria in 2006, while their number has increased to 3000 in 2014. This phenomenon is not unique within Europe. Relocation of economic activity has also been observed recently in other EU countries: Italian firms have moved to Romania and transnational corporations (TNCs) have relocated from Ireland in the first few years after 2007 (Godart et al. 2012; Valdemarin 2015). However, the recent industrial capital flight from Greece is unprecedented at the European level, as since 2007 more than 10,000 firms out of the 835,000 Greek small- and medium-sized enterprises (1.2%) have moved from the country, mainly towards Bulgaria, according to estimations of the Hellenic Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2017). Firm relocation from Greece to Bulgaria started in 1989 with the end of the previous regime and the transition of Bulgaria towards a free market economy (Labrianidis 1997). In the context of economic growth for Greece (3.9% annual average growth rate from 1996 to 2007, according to Eurostat), most businesspeople saw an opportunity to relocate to Bulgaria, seeking market expansion and reduction of operational cost (Bitzenis 2006). To the contrary, other entrepreneurs, mainly the owners of clothing firms, particularly in Northern Greece, moved to cope with competitive pressures and avoid business failure (Karagianni and Labrianidis 2001). However, the socio-economic conditions have dramatically changed since 2007, thus calling for a re-examination of firm relocation.

The next section reviews the literature concerning firm mobility, focusing on the wider incentives and the impact of relocation on business performance. The third section explains the research methodology employed to conduct this research. The following section analyzes the research outcomes, focusing on identifying the main features of firms, such as size, sector, and location, that moved under conditions of economic growth and economic decline. It also examines the effects of the GEC on firm relocation incentives and the impact of relocation on business performance, while also studies the diverse business tactics of Greek entrepreneurs in Bulgaria. In the last section, the conclusions and policy implications are discussed, the limitations of this study are explained and the suggestions for future research directions are framed.

Firm-internal relocation factors and the effects of relocation on business performance

The way that Kiss (2007) has conceptualized firm relocation is particularly suitable for this paper since it focuses on the spatial movement of firms and migration of entrepreneurs rather than foreign direct investment (FDI) and affiliates. Firm relocation is defined as the transfer of “part or all of firm production and/or services to another place” (Kiss 2007, p. 47). It differs from FDI that is related more closely to TNCs, affiliates and managerial control than to small- and medium-sized enterprises and firm migration (Labrianidis 2008). Therefore, theoretical perspectives on firm relocation and migration, which are used synonymously following van Dijk and Pellenbarg (2017), are employed to inform this paper and shape its aims and research questions.

This paper employs arguments of the behavioral theoretical perspective on business mobility as it focuses on firm-internal factors of relocation. The behavioral approach examines the actual behavior of businesspeople, perceiving the enterprises as agents with limited information (Brouwer et al. 2004). It emphasizes the decision-making process, focusing on the individual preferences that play a major role for relocation decisions, which are frequently sub-optimal (Arauzo-Carod and Manjón-Antolín 2004; Meester 2004). On these grounds, the features of the enterprises are crucial for the decision-making procedure related to relocation (van Dijk and Pellenbarg 2000; Arauzo-Carod et al. 2010). Following the behavioral theoretical perspective, the sector, the size, and the location of an enterprise are variables strongly related to relocation decisions (Brouwer et al. 2004; de Bok and van Oort 2011; van Dijk and Pellenbarg 2017).

With regards to firm relocation drivers, in the context of economic growth at the macro level, a thorough scan of the literature has revealed that many entrepreneurs identify an opportunity in moving their firms to counter the fierce competition in the era of trade liberalization (Harrington and Warf 1995; van Dijk and Pellenbarg 2000; Zahra and George 2002; Manjón-Antolín and Arauzo-Carod 2011; Smallbone et al. 2012). However, some entrepreneurs have moved in order to stay in business. This was found in cases of economic decline affecting specific places and economic sectors, including the firms in the industrial district of Como, Italy, and clothing firms in Northern Greece in the 1990s (Karagianni and Labrianidis 2001; Alberti 2006).

Specific elements which are related to the strategy of the firms and determine business mobility (firm relocation incentives) have been identified in the literature. To begin with, most entrepreneurs move to push down the operational cost of the firm (Hayter 1997; van Dijk and Pellenbarg 2000; Domański 2003; Liao and Chan 2009). Strategies for reducing operational cost become more important in the case of economic decline at either the micro or macro level (Godart et al. 2012). Therefore, among these strategies, firm relocation increases in significance as an option for cutting operational cost. Following this strategy, businesspeople frequently move to regions proximate to the home location in order to maintain relations with existing partners and customers (Karagianni and Labrianidis 2001; Kalafsky 2017). Apart from complete relocation, Harrington and Warf (1995) and Wilkinson et al. (2001) have indicated that businesspeople usually move just one part of the firm, predominantly the production, to take advantage of the lower labor cost in the destination territory. Second, market and thus, business expansion constitutes another significant incentive for corporate mobility, as firms must grow in order to improve their performance (Kalantaridis et al. 2011; Carrincazeaux and Coris 2015). Third, businesspeople relocate to enhance the competitiveness of their firms (Labrianidis 2008; Smallbone et al. 2012; Zhu and He 2014). This is of primary importance in the context of the European market integration, which has resulted in more competitive markets (Karagianni and Labrianidis 2001). Apart from relocation, businesspeople could proceed with other major external restructurings in the context of globalization, such as mergers and acquisitions, in order to improve business performance (Warf 2003; Liao and Chan 2009). Finally, scholars have drawn attention to the upgrade of the technological base and product quality (Castells 1996; Kiss 2007). Entrepreneurs aiming at improving the technology of their firms often relocate close to regions with high-skilled labor or areas that are proximate to technological centers.

Overall, businesspeople choose the location of the firm or relocate seeking to derive benefits from their enterprises’ competitive advantage (Harrington and Warf 1995; Aspelund and Butsko 2010; van Dijk and Pellenbarg 2017). By changing the location of the firm, several entrepreneurs respond to the changes of the business environment, seeking to improve its economic performance and level of innovation based on the integration into higher value-added market networks (Sammarra and Belussi 2006; Giner et al. 2017). The also seek to take advantage of the proximity with innovative firms and technological centers and new collaborative corporate systems (Oerlemans et al. 2001). This is related to the determinants of business competitiveness: whether external elements of the company’s functioning are causal factors (Porter 1990) or internal elements should also be considered (Krugman 1996; Bristow 2005). Finally, entrepreneurs make different decisions considering that economic practices greatly vary across space. This variation depends on the geographically-specific economic and institutional context, the internal features of the firms, such as the size, and the characteristics of the entrepreneur (Hudson 2002).

While all these findings refer to the context of global economic growth, it should be considered that business conditions record crucial changes in the aftermath of economic crises. Specifically, the 2007 global economic crisis has significantly affected the performance of firms and has implied major economic changes (Claessens et al. 2012; Godart et al. 2012). On these grounds, this paper examining firm relocation in the aftermath of the GEC, also employs a political economy approach for three reasons. First, this perspective connects the spatial movement of companies with the economic system, its transformations, and its wider processes, such as the crisis (Gertler 2000; Harvey 2006). Second, it examines business mobility through the lens of the broader socio-economic context (Hudson 2002). Finally, this approach considers firm relocation as a dynamic practice, subject to changes caused by underlying forces, such as globalization (Maskell and Malmberg 1999).

Therefore, the works of Harvey (2006) and Hudson (2002) on firm mobility are specifically useful for this paper since they focus on movements of enterprises under conditions of economic recession. Under such circumstances, corporate mobility is among the solutions for entrepreneurs to break free of economic decline by relocating from the territories most acutely affected by the crisis (Hudson 2002). That is, businesspeople seek a “spatial fix” for resolving the crisis (Harvey 2006). They look for locations where the external to the firm socio-economic environment would allow them to restore firm performance and increase the profit rate, taking advantage of the geographical differentiation of socio-economic environment, which includes several interconnected elements (Hudson 2002; Harvey 2006). Among them, labor and transportation cost and taxation are generally perceived as the most important factors that affect business mobility (Hayter 1997; van Dijk and Pellenbarg 2000; Domański 2003).

The theoretical framework, based on the combination of the behavioral perspective with a political economy approach, provides the opportunity to extend our understanding on the effects of the GEC on firm-internal relocation factors and the impact of relocation on business performance, which are the main research goals of this paper. First, it aims at shedding light on the impact of the crisis on firm size, sector, location, and re-organized structure, which have been highlighted as important firm-internal factors of business mobility (Brouwer et al. 2004; van Dijk and Pellenbarg 2017). Second, it attempts to analyze how the crisis has affected the incentives for firm relocation, which are expected to change as business mobility is subject to transformations caused by wider underlying processes, such as globalization and economic decline (Maskell and Malmberg 1999; Hudson 2002). Finally, it seeks to understand the impact of relocation on business performance in the aftermath of the GEC, which is anticipated to be significant (Porter 1990; Bristow 2005).

Survey design

Sampling method and data collection

Responding to the calls of Brouwer et al. (2004, p. 345) for “qualitative research, based on questionnaire and interviews with the actors involved in the relocation process”, a single case study approach based on qualitative research method was chosen. The single case study research strategy was chosen as it facilitates an in-depth analysis of emerging socio-economic phenomena (Bryman 2012). This perspective is also suitable to investigate causal processes (Yin 2014).

Access to data on Greek firms in Bulgaria is extremely difficult since there is no official database of Greek enterprises in the neighboring country, while businesspeople in Bulgaria are not obliged to register their firms with chambers of industry and commerce. The research population includes all the Greek small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) registered in Bulgaria in 2014. There are an estimated 14,000 Greek SMEs in Bulgaria, according to the Bulgarian Commercial Register (2018). The author approached businesspeople who had moved their firms from Greece to Bulgaria between 1989 and 2006, during Bulgaria’s transition towards a free market economy (pre-crisis period), and from 2007, the beginning of the crisis, to 2014, the year that the study was conducted (post-crisis period). Therefore, the initial and basic question was related to the year of relocation. These are the geographical (Bulgaria) and temporal (the period before and after the crisis) boundaries or features of the population.

Considering that this population includes firms that have relocated in two distinct periods which are related to very different socio-economic conditions, the data for the pre-crisis SME relocation could not be aggregated with the post-crisis business movements. Furthermore, it is considered that, apart from the external conditions, the type of relocated firms is also differentiated. Therefore, the potential for systematic bias in the types of firms which moved before and after the crisis is recognized. On balance, the population consists of two different subsets of analysis: the firms that moved to Bulgaria before 2007 and the enterprises that relocated after 2007.

Access to the Bulgarian Commercial Register database was not possible, due to financial restrictions. Ciela, a Bulgarian business software company, provided the author with a list of 11,500 Greek firms in Bulgaria as of the beginning of 2014. Nevertheless, there were no details for 3500 of the enterprises, while around 6000 firms in groups of 200 had the same details: the ones of their tax accounting company. Most of these enterprises were inactive. Indeed, several thousand Greek firms that have been recently established in Bulgaria were found to remain inactive for reasons of tax avoidance, mainly by conducting triangular transactions. Terra and Kajus (2011) have elaborated on triangular transactions: a firm is subjected to the tax regime of the country in which it is registered, regardless of whether it is actually operating there. Overall, only 1500 firms had sufficient data, of which only 600 provided a valid email address. These firms were included in the initial sample frame. According to Ciela’s officials, the enterprises of the list are included in the population of Greek firms in Bulgaria, as laid out in the Bulgarian Commercial Register database.

The present explanatory study draws upon original data collected from an e-survey and fieldwork. The e-survey was carried out in March-August 2014, by sending the questionnaire to all 600 SMEs on the Ciela list with a valid email address. The fieldwork was conducted from May to June 2014. The author attempted to locate Greek firms in the Bulgarian towns based on the Ciela list. However, it was realized that most addresses on the list did not correspond to Greek firms and thus a probability sample became impossible. Subsequently, this list was not helpful, and the author decided to employ multiple sampling methods: non-probability convenience and snowball sampling. This was done by starting the survey with firms that were visually identified by the Greek number plates of cars outside the premises. Before the end of each interview session the author asked the interviewee to name other possible respondents. The networks of social relations that the author built with the respondents were critical for the successful completion of the survey. Therefore, the sample was articulated based on the 600 firms of the Ciela list with a valid email address and the enterprises whose owners participated in the fieldwork survey.

In order to formulate a coherent picture of the phenomenon, this paper combined questionnaires with interviews. Overall, 176 closed questionnaires were completed by owners and managers of Greek SMEs in Bulgaria, which is a quite large sample size, considering the lack of a database. Of the 176 respondents, 73 had moved during the pre-crisis period constituting the first subset of this sample, while the other 103 relocated in the post-crisis period, constituting the second sampling subset. Fifty-five questionnaires were completed in the e-survey, with a response rate of 9%, while 121 participants replied to self-administrated questionnaires. Only 10 out of 131 business people that were asked to participate in the survey of self-administrated questionnaires refused. The closed questions were related to the circumstances in Greece, the incentive to relocate and the new conditions in Bulgaria, alongside the size, sector, and location of the firm. Furthermore, the respondents were asked to evaluate the impact on relocation of the crisis and Bulgaria’s accession to the European Union (EU), on a Likert scale of 1 (least significant) to 5 (most significant). The author delivered the results of the survey to the participants in October 2015, 15 months after the fieldwork. In order to expand the analysis and reveal issues that were indiscernible in the questionnaires, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 72 of the participants in the questionnaire survey, lasting from 30 min to 1.5 h. Sixty-eight interview respondents relocated in the post-crisis period, while four moved before 2007. The entrepreneurs were asked to analyze their business tactics and to describe the drivers of relocation. In addition, four interviews were conducted with owners and managers of tax accounting enterprises and two with representatives of chambers of industry and commerce in Bulgaria, since these organizations have a high level of knowledge regarding the performance of the Greek SMEs in Bulgaria. Notes were kept during all the interview sessions.

This sampling procedure provided accurate results and was efficient for mapping a network of Greek firms in Bulgaria, thereby highlighting significant quantitative and qualitative aspects of this case study, for the following reasons. First, the sampling method, frame and characteristics were well defined (Fowler 2008). Second, Zheng et al. (2006) and Tabachnick and Fidell (2014) have asserted that non-probability sampling of SMEs could provide accurate results due to great difficulties in employing a random sample. Third, the survey was replicated to businesspeople who own firms in all the economic sectors, at a rate similar to the enterprises in Greece and proportional to the Greek firms in Bulgaria (with a prevalence of trade and services and a considerable presence of manufacturing). These estimates were made according to Eurostat and unofficial data from the Greek Embassy in Bulgaria (2014). Finally, according to the same data from the Embassy, the geographical distribution of the sample firms is similar to that of the Greek enterprises in Bulgaria. All these parameters increase the accuracy of the research sample, considering that Greek SMEs constitute a population of firms with quite similar features (Liargovas 1998). Therefore, the potential bias of the snowball sample has been eliminated but should not be ignored in the interpretation of the empirical data.

Data analysis

In processing the questionnaire data and responding to the research questions, descriptive statistics and comparative analysis were used. The author calculated the frequency (%) of firm size, sector, location in Greece and Bulgaria, firm structure that is re-organized and the incentive to relocate. Furthermore, the frequency of each value of the Likert scale regarding the impact of the crisis and Bulgaria’s accession to the EU on relocation was estimated. The results of the pre-crisis movements were compared to these of the post-crisis period, in order to explain the direct effects of the GEC on business mobility.

In order to deepen the analysis and provide stronger evidence for the two first research questions, the author investigated the relationship of the economic sector, location, firm structure that is re-organized, relocation incentive, and size of the enterprises with the period of relocation. This relationship was examined by employing the Pearson Chi square test which is suitable to test hypotheses related to the association between two variables (Bors 2018). Specifically, a continuity correction test was employed and the p value was assessed. The firms were divided into two groups: pre- and post-crisis relocated enterprises. Both groups had more than five observations, thus satisfying the minimum requirement to run Chi square analysis for reasons of statistical validity (Bors 2018). Following Bitzenis and Marangos (2008), the results were tested at 1, 5 and 10% levels of significance in order to reject or accept a hypothesis, based on the p value. Therefore, p values higher than 0.01, 0.05 and 0.1 confirm the null hypothesis (Ho) of no association between the two variables at the respective level of significance. By contrast, p values lower than 0.01, 0.05 and 0.1 confirm the alternative hypothesis (Ha), according to which the two variables are associated at the respective level of significance.

Qualitative analysis was employed to analyze interview data, thereby comparing the research arguments and theoretical propositions with the empirical evidence (Fowler 2008). Initially, all the interviews were manually reproduced (32 h of digital recording). Thereon, the most relevant parts were selectively transcribed employing the verbatim transcription technique. In order to establish the trustworthiness of the transcripts, the emotional context, the body language, and the sentiments expressed by the respondents were also considered (Halcomb and Davidson 2006). After combining the transcriptions with the field notes and before finalizing the quotes, the author checked for common themes in the manner that the respondents self-described their business tactics, thus systematizing and synthesizing themes from their responses. Finally, the quotes were chosen as examples of a representative response.

Empirical analysis

Comparing business features between the pre- and post-crisis period

A significant increase in the number of Greek firms operating in Bulgaria has been observed since 2007. The respondents were asked to estimate the number of Greek firms that are active, since they have high knowledge of the phenomenon, operating their enterprises and living in Bulgaria. As estimated by them, in 2006, approximately 1000 Greek firms were located in Bulgaria, while in 2014 there were around 3000 Greek enterprises located in the neighboring country (Kapitsinis 2017). Most firms in both periods were SMEs, according to the representatives of the chambers of industry and commerce. While there was an equal distribution of firm size in the pre-crisis period, since 2007 micro firms have been dominant (Table 1), emphasizing the importance of firm size in relocation decisions (Brouwer et al. 2004; van Dijk and Pellenbarg 2017). Indeed, the Greek micro enterprises have been greatly influenced by the crisis (Dimitropoulou et al. 2014), and thus their owners recorded a higher tendency for relocation. The p value in the Chi square analysis confirms this evidence since it is lower than 0.01. Thus, the Ha hypothesis is accepted, and firm size is associated with the period of relocation at 1% level of significance. While the small size of an enterprise, and the subsequent limited resources, constrain its ability to internationalize (Aspelund and Butsko 2010; de Bok and van Oort 2011), the statistical analysis reveals a high tendency of small firms to relocate to a foreign country, due to the impact of the recession on their performance.

Interesting results were found with respect to the geographical distribution of the firms. In the pre-crisis period, the vast majority of entrepreneurs (80%) relocated from the Greek border or near-border regions such as Thessaloniki, Serres and Drama, taking advantage of the geographical proximity of these areas to Bulgaria (Fig. 1). Accordingly, the majority of the Greek SMEs relocated to the border region of Blagoevgrad (Fig. 2) and, specifically, to the towns of Petrich, Sandanski and Blagoevgrad and the villages of Melnik and Marikostinovo. A smaller number relocated to the capital region of Sofia, which offers the biggest market and the highest quality infrastructure (Karafotakis 1999). Similar results have been provided by Karagianni and Labrianidis (2001) on Greek firm relocation to Bulgaria in the 1990s.

By contrast, during the post-crisis period, the phenomenon has spread throughout Greece. A feature that might strike the reader is that the rate of enterprises leaving the border regions has declined to 64% (− 20%) of the firms relocated after 2007, while the number of firms moving from the Attiki capital region has considerably increased, as this region has been greatly affected by the crisis (Giannitsis 2013). Additionally, several enterprises have left regions of the Greek mainland (for instance Achaia, Arta and Fthiotida), highlighting the escalation of the phenomenon and the impact of the crisis on all Greek regions. In Bulgaria, most Greek SMEs were still located in Blagoevgrad and Sofia regions. However, the Chi square analysis did not confirm the Ha hypothesis, since the p value is higher than 0.1 (0.31 for location in Greece and 0.74 for location in Bulgaria). Consequently, the null hypothesis is accepted, and the location of firms in Greece and Bulgaria is not associated with the period of relocation. In other words, the Chi square analysis indicates that the entrepreneurs have moved mainly from the Greek border areas in both periods, taking advantage of the geographical proximity that would allow them to remain close to existing partners and customers and export to proximate markets (Karagianni and Labrianidis 2001; Kalafsky 2017).

Table 3 indicates the economic sector of the firms surveyed, revealing major differences between the pre- and post-crisis period. From a statistical perspective, the p value is 0.0001 and thus lower than 0.01 (Table 2). Therefore, the Ha hypothesis is accepted, meaning that the period of relocation and the firm sector are interrelated at 1% level of significance. Before 2007, manufacturing firms were the most common, followed by trade enterprises. As expected, among manufacturing enterprises, clothing firms were dominant. Indeed, Karagianni and Labrianidis (2001) have underlined the big exodus of most clothing firms from Northern Greece to the Balkan economies in the 1990s, on the grounds of the significant increase of the competitive pressures. In the post-crisis period, a more equal distribution of the SMEs across the economic activities was recorded, as the crisis has affected all economic sectors (Giannitsis 2013). First, the Greek clothing sector, and thus manufacturing, in Bulgaria has shrunk. According to the representatives of the chambers of industry and commerce in Bulgaria, many manufacturers had already relocated to more profitable territories, especially to Asian emerging economies, forming part of the wider European business movements to these countries, which increased during the 2000s (Pickles and Smith 2011). Second, the proportion of firms engaged in construction and tertiary sectors (trade, mainly in clothes and food, as well as accommodation and food service activities) has significantly increased. In fact, the crisis has affected all sectors in Greece (Giannitsis 2013), thus driving the owners of the companies to seek for a spatial fix by moving to Bulgaria, as indicated by the statistical analysis. Particularly, enterprises in the tertiary sector represent the 63% of the sample firms which moved after 2007. The high rate of firms in the tertiary sector is a similar picture to the Bulgarian economy: almost 80% of the Bulgarian firms are active in the tertiary sector (Eurostat data). This evidence shows that the firms moving from Greece are active in sectors that directly compete with local Bulgarian firms. This claim is supported by the fact that 45% of enterprises which moved in the aftermath of the GEC address solely the Bulgarian market and are not engaged with export activity. Overall, the results of Table 3 emphasize the importance of firm sector in relocation decisions, which have been found to be closely associated (van Dijk and Pellenbarg 2000; Arauzo-Carod and Manjón-Antolín 2004).

Furthermore, the research findings demonstrate a crucial transformation of business activities along with the relocation in the post-crisis period, with many businesspeople switching to accommodation and food service activities. Particularly, respondents perceived the strong presence of Greek entrepreneurs and students in Bulgaria as an opportunity to provide food services to them. When asked about the decision to relocate to Petrich in 2014, the owner of a food service enterprise said: “I opened my tavern here as there are many Greek people. In Greece, I owned an automobile repair store.” Setting up a food service firm does not require a significant amount of seed capital, is not a risky investment and, thus, is quite popular among Greek businesspeople. The decisions behind these changes are opportunistic and not well-planned, indicating short-termism, a basic characteristic of the Greek entrepreneurial mentality (Caloghirou 2008; Giannitsis 2008). Overall, many Greek businesspeople focus on speculative activities with cheap and low-tech products and cut-rate services with low business risk, neglecting long-term and sound business strategy, while seeking to make quick and easy profits (Papagiannakis 2008).

Accordingly, this sectoral change has also affected the firm structure that is re-organized (Fig. 3). That is, many entrepreneurs, having closed their firm in Greece, established a new one in a different economic sector in Bulgaria, in the post-crisis context. These interviewees, when asked to provide details about the firm structure that is re-organized, were among those who chose the response “None of these. My firm was always Bulgarian”. Therefore, most of the businesspeople included in this category have treated the change of the branch of the firm or the name of the enterprise not as relocation, but as the establishment of a new firm. The results were estimated by accounting for these businesspeople, as the number of respondents who were engaged in business activity for the first time in Bulgaria, also included in this category, was limited.

Overall, most entrepreneurs moved the whole enterprise, ceasing operations in Greece and setting up a new firm in Bulgaria, in both the pre- and post-crisis periods. Indeed, the Chi square analysis supported this result, thus rejecting the Ha hypothesis, as the p value (0.21) is higher than 0.1. Therefore, the firm structure that is re-organized is not associated with the period of relocation and the crisis has not affected the specific kind of relocation. The statistical analysis highlights that, in both periods, the businesspeople chose complete relocation to solve their problems caused by the business conditions in Greece that have never been favorable. Indeed, Greece historically demonstrates ineffective state policies and tax system, high levels of rent-seeking, corruption and clientelism and fragile social trust (Caloghirou 2008; Papagiannakis 2008). These conditions have further deteriorated since 2007 due to the GEC and the austerity policies that the Greek government implemented (Giannitsis 2013).

The analysis demonstrates that 18% of the respondents who relocated in the pre-crisis period, moved just one part of their firm, primarily the production branch, in order to benefit from the low labor cost in Bulgaria. In fact, labor cost is widely recognized as the most important relocation factor, since it considerably affects the total operational cost of an enterprise (van Dijk and Pellenbarg 2000; Domański 2003; Sammarra and Belussi 2006; Kiss 2007; Zhu and He 2013). Providing similar evidence, Karagianni and Labrianidis (2001) have shown that approximately 40% of Greek enterprises in Bulgaria were involved in partial relocation seeking to cope with the rise of competitive pressures in the 1990s, similar to other firms (Smallbone et al. 2012; Zhu and He 2014).

However, the socio-economic environment in Greece has significantly deteriorated since 2007. Contrary to the pre-crisis period evidence and suggestions in the literature (Wilkinson et al. 2001; Smallbone et al. 2012), the tendency for partial relocation has declined by 50% (just 9% of the respondents who moved after 2007). That is, the entrepreneurs did not favor any business activity, even just the operation of a managerial branch, within the hazardous conditions in Greece. When asked about the decision to relocate to Blagoevgrad in 2010, a respondent explained: “I could not make it in Greece. Why continue having even part of my enterprise there?” Moreover, a small number of subsidiaries (10%) was found in the post-crisis period. The very small size and low level of financial resources of the Greek SMEs were important for the decision to relocate rather than to set up an affiliate. Considering that firm size and relocation decisions are closely interrelated (Aspelund and Butsko 2010; de Bok and van Oort 2011), it is worth noting that the small size and the subsequent low level of financial resources of the Greek SMEs were important for the decision to relocate rather than to set up an affiliate. Businesspeople’s limited ability to be both in Greece and Bulgaria to manage the enterprise was determinant.

Finally, the findings indicate that many businesspeople who moved in the post-crisis period (37%) have established a firm in Bulgaria without closing their enterprise in Greece. This is considered a firm expansion, albeit not the typical kind, on the basis that the firm in Greece was often inactive. The respondents made the decision not to close the enterprise in Greece to facilitate exports and pay off any possible debt. This was clearly the case for an interviewee who established a trading firm in Sofia in 2010 and stated: “I was obliged to keep my firm in Greece in an inactive mode, to pay off my debts.” Additionally, some entrepreneurs maintained their firm in Greece because firm closure procedures are time-consuming, especially in the case of large debts to the government or the banks. By contrast, during the pre-crisis period, businesspeople expanded their firms to Bulgaria, mainly in the banking and food industries, to boost business growth, in the wider context of economic optimism (Karagianni and Labrianidis 2001; Bitzenis 2006).

The impact of the crisis on relocation incentives: business growth versus survival

Half of the respondents that moved between 1989 and 2006 were seeking market expansion and lower operational cost (Fig. 4), which have been indicated as important relocation incentives (van Dijk and Pellenbarg 2000; Domański 2003; Liao and Chan 2009; Smallbone et al. 2012). They perceived relocation as an opportunity for higher profits and firm expansion. These respondents owned firms primarily in trade and construction. The work of Labrianidis (1997) is helpful in understanding that relocation was only part of wider restructurings, which Greek entrepreneurs adopted to boost firm competitiveness. Other strategies were related to labor cost reduction, mergers, and buyouts. The opening of the Balkan economies and the low degree of penetration of Western European TNCs created an environment that was identified by Karagianni and Labrianidis (2001) as an opportunity for Greek businesspeople to expand their markets to the neighboring country. This research outcome concurs with findings in the literature related to other cases, including German firm relocation to Central Europe and movements of Japanese electronics firms to Malaysia (Pavlínek and Smith 1998; Wilkinson et al. 2001; Manjón-Antolín and Arauzo-Carod 2011). When asked about the decision to enter the Bulgarian market, a respondent who has been running a firm in Melnik since 2004 emphatically noted: “It was my choice to invest in Bulgaria. It was an opportunity to expand the markets of my enterprise.”

Looking at Fig. 4, one is especially struck by the fact that the remaining half of the respondents who relocated before 2007 were found to be striving for firm survival. This research outcome confirms that the business environment in Greece has never been favorable, owing to the inferior position of Greece in the global division of labor and Greece’s weak institutions (Caloghirou 2008; Giannitsis 2008). Nevertheless, given the conditions of economic growth at the macro level in Greece during that period, it was far from expected that so many entrepreneurs would have moved their firms in order to stay in business. Most respondents who relocated to Bulgaria before 2007 to avoid business failure owned manufacturing firms (64%). Providing similar results, Karagianni and Labrianidis (2001) have indicated that in the clothing sector, firm survival constituted the main incentive for relocation from Greece to Bulgaria in the 1990s. Tending to base their products’ competitiveness on price, these firms’ owners experienced strong competition from the EU Core as well as emerging economies because of the European economic integration and trade liberalization in the late-1980s (Labrianidis 1997). At that time, subsidies and grants for exports, restrictions, and duties on imports from developing countries and therefore, protectionism of the Greek economy were abolished. The commodities produced by the Greek firms could compete neither with those of the developed economies in terms of quality, nor with those of the developing economies in terms of price. Subsequently, entrepreneurs found a way to break free of economic decline by moving, often partially, their firm or subcontracting enterprises in Bulgaria, seeking operational cost reduction that was vital for firm survival (Karagianni and Labrianidis 2001). Providing similar evidence, Alberti (2006) has indicated that firm exit from the industrial cluster of Como in the late-1990s was a necessity, as the specific area recorded rapid economic recession.

The conditions in Greece have significantly changed since 2007. Considering that the wider socio-economic context under which firms operate has significant effects on firm mobility (Hudson 2002; Harvey 2006), it could be argued that the escalation of the phenomenon of relocation from Greece to Bulgaria is largely attributed to the severe impact of the GEC and the way that the Greek government attempted to resolve it. In 2010, Greece was excluded from the international financial capital markets and the government decided to implement stringent austerity policies to achieve fiscal balance. Landmark measures involved a rise in taxation (an increase of business tax rate from 20% in 2011 to 26% and implementation of exceptional taxes), cuts in wages and pensions (25% reduction of labor cost, the greatest in the EU from 2010 to 2013), and the abolition of collective agreements. These policies formed part of a rescue plan under the directives of the European Central Bank, the European Commission, and the International Monetary Fund, while another similar plan was agreed upon in 2012 (Kapitsinis et al. 2013).

The crisis and austerity policies have entailed higher taxation, a lack of external financing, a drop in demand, and a collapse of trust within Greek society, which in turn, have deepened the economic decline (Giannitsis 2013). All these circumstances have made the Greek socio-economic environment quite hazardous for SMEs. Considering in addition their low competitiveness and family character (Liargovas 1998), the impact on Greek SMEs was bound to be important. The operational cost rose, and revenues fell, while credit was not extended. Subsequently, SMEs were in a strenuous position with massive debt (€193 billion or 93% of GDP) and drop in profits, thus recording high bankruptcy risk. In the context of the crisis, the number of Greek SMEs declined by 25% (228,000 fewer firms) from 2008 to 2014 (Ministry of Finance 2017), while other businesspeople decided to move from Greece.

The crisis and government policies have driven the decision of most respondents (86%) to relocate to Bulgaria after 2007. The economic downturn and the vicious cycle of austerity had significantly affected firm operation, as capital could not be circulated profitably. Businesspeople did not favor the socio-economic conditions in Greece and reacted against falling profits by moving to Bulgaria in order to avoid economic decline and firm bankruptcy. Research outcomes demonstrate that most respondents (67%) would not have relocated from Greece if the crisis had not occurred. When asked about the decision to move to Bulgaria, a respondent in Petrich stated: “I would have no reason to relocate if the crisis had not occurred and the Greek government had not implemented these policies.”

Therefore, contrary to the balanced picture of the pre-crisis period, the primary relocation incentive for 71% of the surveyed entrepreneurs who moved after 2007 was to keep their business going and secondly, to turn it around (Fig. 4). From a statistical point of view, the p value is 0.02 and thus lower than 0.05. As such, the Ha hypothesis is accepted, meaning that the period of relocation and firm relocation incentive are interrelated at 5% level of significance. In other words, the Chi square analysis confirms that the GEC has affected the wider firm relocation incentive. Greek businesspeople sought a spatial fix for escaping from the Greek post-crisis economic and institutional environment and restoring profits. In describing the spatial fix, Harvey (2006) and Hudson (2002) have argued that space is essential in businesspeople’s efforts to avoid economic decline and increase the falling profit rate. The manager of a tax accounting company in Petrich said: “since 2007, Greek entrepreneurs have been moving to Bulgaria to survive and restore profits.” The owner of a construction enterprise in Blagoevgrad added: “I moved to Bulgaria to escape from decline, keep my firm running and increase my profits.”

Despite businesspeople’s efforts to resolve the crisis by reducing operational cost, most frequently through dismissals and labor flexibilization, business performance had not improved since conditions deteriorated as time passed, thus making external restructurings, such as relocation, necessary. Relocation emerged as a necessity to stay in business by drastically pushing down the operational cost in Bulgaria. The manager of a manufacturing firm in Sofia mentioned: “we were obliged to relocate and change lifestyles to maintain business and start improving firm performance.” The owner of a construction firm in Marikostinovo added: “I was desperate, just seeking to keep the business running.” The businesspeople decided to relocate, rather than abandoning entrepreneurship. The owner of a small trade firm in Sofia, established in 2014, stated: “This is what I can do, nothing else.” A self-employed respondent who moved to Sandanski in 2013 added surprisingly: “I came here to earn more money. I prefer being a business owner in Bulgaria rather than an employee in Greece, even with a salary of €2,500.” Many respondents would have had to cease operations if they had not moved, thus perceiving relocation as a necessity, as they faced high bankruptcy risk in the post-crisis period. This result is crucial for economic geography literature where the claims about opportunity-driven firm mobility in the context of economic growth flourish (Pavlínek and Smith 1998; Domański 2003; Wright et al. 2007; Smallbone et al. 2012).

The results show that for most respondents the decision to move from Greece in the post-crisis period did not form part of a long-term strategy that would focus on quality improvement. For instance, many entrepreneurs collected rough information on Bulgaria’s market quickly and extemporaneously on their own or from asking friends. By contrast, Wilkinson et al. (2001) and Zahra and George (2002) have described well-planned relocation decisions within a wider strategy of long-term investment to boost firm competitiveness and improve product quality, in the context of economic growth. However, within a recessionary environment, only 29% of the respondents relocated in pursuit of market expansion and reduction of operational cost, which studies indicated to be crucial incentives for opportunity-driven firm relocation, under conditions of economic growth (Kalantaridis, Vassilev, and Fallon 2011; Carrincazeaux and Coris 2015). The owner of another tax accounting company said: “a small number of entrepreneurs have other goals, such as product upgrade.”

However, differences in incentives were found among the respondents that moved in the post-crisis period. The owners of 76% of micro and 52% of small enterprises would not have relocated to Bulgaria if the crisis had not occurred, as these firms have been most acutely affected by the crisis and austerity policies (Dimitropoulou et al. 2014). By contrast, most owners of medium-sized firms (66%) would have moved to Bulgaria even under conditions of economic growth. Specifically, the owner of a medium-sized firm in Marikostinovo explained: “It was a decision that I planned for a long time. I would relocate to Bulgaria anyway to test the market and the level of my sales.” Additionally, most entrepreneurs in manufacturing (52%) would have relocated even if the crisis had not occurred, while owners of trade (80%) and services (72%) firms would not have moved to Bulgaria if economic growth had continued, suggesting that the Greek manufacturing sector has been slightly more resilient than the tertiary sector in the post-crisis period.

Differences in the relocated firms: true entrepreneurs versus survivors

Departing from these observations, the author decided to disaggregate the results and divide the businesspeople into two distinct groups according to their wider incentive and motivation for relocation (Table 4). The first group involves the businesspeople who perceived relocation as an entrepreneurial opportunity seeking economic growth and market expansion. They own big, strong, and productive firms, having moved in both the pre- and post-crisis periods, and are called the “true entrepreneurs”. The second group involves the owners of small, weak, and unproductive enterprises who perceived relocation as a necessity to avoid business failure. This group, which is called the “survivors”, was dominant in the post-crisis period (71% of all businesspeople who have relocated since 2007 according to Fig. 4). Five specific points are worth our attention.

First, the size of the enterprises is closely related to the type of their owners and thus the incentive for relocation, as firm size significantly affects relocation decisions (Brouwer et al. 2004; de Bok and van Oort 2011). The true entrepreneurs, in both periods, demonstrate high levels of medium firms (33% in the pre-crisis period and 20% in the post-crisis context), compared to the survivors (just 5%). By contrast, the survivors own mainly micro firms (72%), whereas only 36% (pre-crisis) and 45% (post-crisis) of true entrepreneurs employ less than 9 people. This is an important finding considering that 98% of the Greek firms were micro enterprises in 2009 (Eurostat).

Second, access to credit has been necessary for the majority (70%) of the survivors, while it has not been necessary for over a half of the true entrepreneurs. Most survivors (45%) have used loans to pay taxes, wages, and utilities, i.e. to fund their working capital, as they mainly own micro firms (Labrianidis and Vogiatzis 2013). By contrast, only a minor part of the true entrepreneurs (20% -pre-crisis- and 25% -post-crisis) have used external funds to finance their working capital, as they manage larger and stronger firms which are more productive than the firms of the survivors.

Third, most survivors (54%) moved their firms to the border region of Blagoevgrad due to geographical proximity. Only 25% of the survivors relocated to Sofia which has the biggest market in Bulgaria (Karafotakis 1999). By contrast, over a half of the true entrepreneurs moved to Sofia (51% in the pre-crisis context and 50% in the post-crisis period), since their stronger firms can cope with the competition.

Fourth, 72% of the survivors completely moved to Bulgaria as they could not sustain any business activity in Greece, while only 36% -pre-crisis- and 20% -post-crisis- of the true entrepreneurs chose the complete relocation. Consequently, most true entrepreneurs still own a firm in Greece, while 68% of the survivors do not. This could be explained by the fact that the micro firms, which are managed mainly by survivors, were most acutely affected by the crisis and austerity policies (Dimitropoulou et al. 2014). Moreover, this finding could possibly be a consequence of the limited financial resources that the survivors have, as they mainly own micro enterprises (Aspelund and Butsko 2010; de Bok and van Oort 2011). Therefore, only 1.5% of the survivors’ firms are subsidiaries, whereas 20% of the true entrepreneurs that relocated in the pre-crisis period and 37% of the true entrepreneurs who have moved since 2007 own subsidiaries.

Finally, if the crisis had not emerged the employed business tactics between the true entrepreneurs and the survivors really present a great contrast. On one hand, the vast majority of the survivors (81%) would not have moved if the GEC had not unfolded, revealing the necessity-driven decision for relocation. On the other hand, 71% of the true entrepreneurs stated that they would have moved even without the crisis, since they perceived relocation as an entrepreneurial opportunity for market expansion and reduction of operational cost.

Overall, there are many similarities between the types of the firms regardless of the period that they moved. In other words, the businesspeople that own strong and productive firms and relocated in the post-crisis period record more similar findings with the true entrepreneurs that moved in the pre-crisis period rather than with the survivors who have relocated since 2007. The latter own small and weak firms of low productivity and competitiveness.

The socio-economic environment in Bulgaria

Apparently, most respondents moved to Bulgaria to reduce the operational cost by taking advantage of the different socio-economic conditions to Greece. The Bulgarian state, which seems more business-friendly than the Greek, has been an “active agent” for FDI in the last 25 years, like most states in Central and Eastern Europe (Hudson 2002). That is, it has been making efforts to create suitable circumstances for attracting foreign firms by providing incentives related to low taxation and labor cost and high formal institutional capacity (Slaveski and Nedanovski 2002; Bitzenis 2006). These conditions have attracted Greek entrepreneurs in the pre-crisis period.

In the aftermath of the 2007 GEC, Greek businesspeople relocated to Bulgaria because of the way the crisis developed in the neighboring country and was dealt by the state. Indeed, the Bulgarian economy has been less affected by the crisis, while the government has adopted less stringent austerity measures than the Greek one, focusing on cuts in public expenditures, which had no severe effects on the Bulgarian economy (Petkov 2014). After a sharp decline in GDP in 2009 (− 3.6% GDP growth from 6% in 2007), the Bulgarian economy recovered (1.3% GDP growth in 2010 and 1.9% in 2011), whereas unemployment rate recorded a more significant impact (13% in 2013 from 6.9% in 2007), but less important than the one in Greece (Eurostat).

Since 2007, Bulgaria has regulated the lowest corporate tax rate (10%) and minimum wage (16% of the EU average) in the EU, which allowed the Greek businesspeople to greatly reduce the operational cost. Additionally, the Bulgarian state provides electronic governance, thus paving the way for low-cost transactions with citizens. Greek entrepreneurs seem to have coped with existing corruption in Bulgaria, since they have had ample experience with it in Greece (Giannitsis 2013). Consequently, the Bulgarian socio-economic environment allowed the reduction of operational cost, which was greater in the post-crisis period. A relocated firm’s operational cost dropped by 40% on average before 2007, while in the post-crisis period the decline was even greater (60%), as since the late-2000s the Greek business environment has become more expensive.

Finally, the relocation decision of most entrepreneurs (71%) was significantly affected by Bulgaria’s accession to the EU in 2007. This was an important development for Bulgaria, resulting in open borders and trade liberalization with the rest EU member states and a partial improvement in the institutional environment (Pashev 2011). Several scholars have indicated that the accession of Central and Eastern European states to the EU has facilitated the entry of Western European firms into their markets (Hudson 2002; Jürgens and Krzywdzinski 2009). A respondent who runs a construction firm in Blagoevgrad said: “I moved after 2007, as Bulgaria’s accession to the EU was added to the very low operational cost.”

The impact of relocation on SME performance: the importance of business strategies

Considering the significant problems that the entrepreneurs faced in Greece and their decision to resolve them by relocating, it is important to examine the implications of their tactics on firm performance and competitiveness, especially in the post-crisis period. Certainly, the change of external socio-economic conditions was crucial. The great reduction of the operational cost, as a result of the lower labor and transportation cost and taxation, is the most beneficial development for most entrepreneurs surveyed (92%), thus lessening the necessity of external finance and boosting revenues. However, in the new Bulgarian socio-economic context, a question arisen is related to whether the low operational cost was sufficient to secure SME survival. Based on the division between true entrepreneurs and survivors (Table 4), evidence about business tactics and performance in Bulgaria is provided in Table 5.

Seeking to explain the diverse findings related to firm performance after the relocation to Bulgaria, it is worth noting the various business tactics recorded by the different types of Greek businesspeople. Most true entrepreneurs (50% in the pre-crisis period and 35% in the post-crisis context) address several markets apart from the Greek and Bulgarian ones. Indeed, many respondents from this category sought the integration into new market and coordination networks, attempting to export to Western Europe, despite the difficulties that SMEs face for export activities (Kalafsky 2017). It is worth noting that a minor part of the true entrepreneurs (6.67% in the pre-crisis context and 4.35% in the post-crisis period) targets solely the Greek market. This indicates that, after the relocation to Bulgaria, they proceeded with internal changes to their firms, which are crucial for improving business competitiveness (Krugman 1996; Bristow 2005; Sammarra and Belussi 2006).

Other important internal changes include the development of new products, the improvement of product quality, and the introduction of innovation. For instance, in boosting firm competitiveness, apart from relocation, the owner of a manufacturing enterprise in Sofia implemented internal changes, claiming: “Relocation affected my entrepreneurial mentality, as in Bulgaria I trade new products of higher quality. This was crucial to the success of the firm.” Moreover, an entrepreneur who operates a trading firm in Petrich stated: “I added services to improve the competitiveness of my firm, such as free shipping of products to Greece.” Finally, the owner of a trading firm in Blagoevgrad has focused on improving product quality: “I am, primarily, interested in the quality and, secondarily, in the price of my products. In the absence of external finance, I am much more careful in what and how much I buy.”

These business tactics have affected the performance of the firms owned and managed by the true entrepreneurs. These internal to the firm changes, alongside the new socio-economic conditions in Bulgaria, have led to economic recovery for these enterprises. Considering in addition, the high productivity of these firms, it is not surprising that they record the highest rate of performance improvement in Bulgaria. Specifically, 33% of the true entrepreneurs that moved in the pre-crisis period stated that they improved the performance of their enterprises partially, while 56% of these businesspeople improved it greatly. Moreover, 31% of the true entrepreneurs that have relocated since 2007 said that they have improved business performance partially and 54% have improved it greatly.

By contrast, the survivors moved their firms, primarily involved in low value-added micro-trade activities, to Bulgaria, as a reactive decision with no intention of making internal changes, seeking solely firm survival rather than quality improvement. Indeed, many respondents disconnected the decision to relocate with efforts to upgrade the technology or improve the quality of products and services, despite the fact that businesspeople frequently relocate seeking to upgrade the quality of goods (Castells 1996; Smallbone et al. 2012). The lack of such plans is related to the poor SME performance, respondents’ eagerness to break free of the Greek post-crisis institutional and economic environment, and the Greek entrepreneurial mentality. Regarding the latter, most Greek businesspeople lack strategic planning and neglect product quality, circumventing occasional falling sales by cutting costs and adopting defensive and short-term business tactics that usually rest on tax avoidance through clientelist relations with state officials (Caloghirou 2008).

The survivors believed that relocation would solve all their problems. For instance, many survivors (23%) address only the Greek market, despite the great drop in demand, while only 19% target a market apart from the Greek and Bulgarian ones. This highlights that most survivors, having low entrepreneurial skills and expectations, typical of a Greek SME owner (Caloghirou 2008), neglected the integration into new market and coordination networks, expecting that relocation would restore firm performance on its own. This finding highlights that relocation has not affected their business performance. On these grounds, they overlooked, or were incapable to apply internal changes to their enterprises. For instance, the owner of a food service firm in Petrich did not manage to overcome financial hardship by simply targeting the increasing population of Greek entrepreneurs in Bulgaria, as neither the latter’s support nor their long term stay in Bulgaria should be taken for granted. Moreover, the same entrepreneur accentuated: “I have not made changes internal to the firm, a fact that deteriorated its performance.” On these grounds, the business operations of survivors in Bulgaria are not considered long-term. Unsurprisingly, they record the smallest rate of entrepreneurs (48%), who improved the economic performance of their enterprises considerably.

As noticed in the second visit to Bulgaria, 15 months after the fieldwork, the great reduction of operational cost allowed most sample firms (75%) to survive. The majority of them recorded neither an improvement nor a deterioration of their performance. However, 25% of the firms surveyed were shut down in Bulgaria. Most of them were managed by survivors. This firm closure rate is much higher than the enterprise death rate in Bulgaria (13%) in 2013–2014 (Eurostat data). These results underline the great vulnerability of the Greek SMEs in a foreign environment. On balance, the true entrepreneurs combined relocation with internal changes and achieved the fastest recovery and growth of the enterprise, while many survivors struggle to maintain business in Bulgaria. These findings contrast with the arguments of Porter (1990) and back the claims of Krugman (1996) and Bristow (2005), revealing the complex relationship between internal and external elements and the way it affects business competitiveness. While space and territorially-specific socio-economic conditions are crucial for the performance of the enterprise (Porter 1990), factors related to the core of the firm are just as important (Krugman 1996; Bristow 2005).

The moderate business performance is among the reasons that the increased registration of Greek SMEs to Bulgaria in the post-crisis period has not benefitted the Bulgarian regional economies as much as expected. Other reasons are related to the inactive firms and to the fact that many entrepreneurs transfer part of the value produced in Bulgaria back to Greece to pay debts. By contrast, the negative impact on the Greek regions has been much more important. Consequently, regions in Southern Bulgaria that attracted the largest number of Greek SMEs have recorded among the lowest economic growth rates in the country since 2010, according to Eurostat data. On the other hand, the regions of Northern Greece, where many firms used to be located, demonstrated among the highest unemployment and recession rates in crisis-ridden Greece.

Conclusions

This paper has examined the relocation of Greek SMEs to Bulgaria under conditions of economic growth and decline at the macro level, in order to understand the impacts of the GEC on firm-internal factors of business mobility and the effects of relocation on business performance. Before reflecting on the findings, it is essential to reiterate the limitation of this paper: interviews on a limited number of SME owners and managers were conducted, attributable to the restricted availability of data, which is the biggest obstacle in studying Greek firms that operate in foreign countries. For this reason, the survey sample was purposive and the results present limitations regarding their generalization.

The analysis of this paper highlighted significant differences related to firm-internal relocation factors between the pre- and post-crisis period. In both periods, most businesspeople moved the whole firm from Greece to Bulgaria. However, differences uncovered the considerable impact of the 2007 global economic crisis on firm relocation. Indeed, a brief overview of the findings leads to the conclusion that the GEC and the policies implemented to resolve it had a crucial impact on firm-internal factors of business mobility, thus contributing to the firm relocation literature (Domański 2003; Brouwer et al. 2004; Kiss 2007; Labrianidis 2008; van Dijk and Pellenbarg 2017).

In the pre-crisis period, there was an equal distribution of the size of Greek SMEs in Bulgaria, while most of them were active in trade and manufacturing. Relocation was perceived as an opportunity for many Greek entrepreneurs to expand the market and restore competitiveness, similar to business movements in other case studies (Pavlínek and Smith 1998; Wilkinson et al. 2001; Smallbone et al. 2012). What is of uppermost importance is that many SME owners could solve their problems in Greece by internal restructurings, including dismissals and cuts in investments.

While before 2007, businesspeople considered relocation necessary only in specific sectors and regions which recorded economic decline, such as the firms in the industrial district of Como, Italy (Karagianni and Labrianidis 2001; Alberti 2006), since 2007, relocation from Greece to Bulgaria was perceived as a necessity for most entrepreneurs in all the regions and economic sectors. The Greek SMEs in Bulgaria were distributed more equally across the economic sectors than in the pre-crisis period, as the GEC has affected all economic sectors. Contrary to the pre-crisis evidence, the micro enterprises were dominant among the Greek SMEs in Bulgaria, as these firms were mostly affected by the economic decline in Greece. These results highlight the strong correlation of business mobility with factors internal to the firm, such as size, sector, and entrepreneurial strategy (van Dijk and Pellenbarg 2000; Brouwer et al. 2004).

Most businesspeople would have had to cease operations if they had not relocated, owing to the high bankruptcy risk in Greece. They moved in an effort to avoid business failure by breaking free of the Greek business environment. The latter considerably deteriorated as a result of the GEC and government policies. Indeed, businesspeople’s decision to relocate was greatly influenced by the political choices of the Greek government that focused on austerity measures to achieve fiscal stability, entailing a rise in taxation, a drop in demand, a collapse of social trust and a lack of external finance. Greek businesspeople relocated to Bulgaria in order to maintain business by significantly reducing the operational cost. That is, they sought a spatial fix for resolving the crisis (Harvey 2006).

In conclusion, the post-crisis relocation of Greek SMEs is different to the case of the TNCs moving around the globe, and of the strong SMEs internationalizing to expand their markets, in the context of economic growth (van Dijk and Pellenbarg 2000; Zahra and George 2002; Wright et al. 2007; Smallbone et al. 2012). Therefore, this paper enriches the academic discourse on business internationalization, by highlighting the case of firm survival: many entrepreneurs decided to internationalize to avoid business failure, instead of closing their firms or working as employees. The decision to relocate was not related to the incapability to produce cheap products or to provide low-cost services in Greece but to the inability to pay daily operations, including salaries and taxes.

However, apart from the changes in the business environment, there are differences in the composition and type of entrepreneurs. The analysis of this paper suggested a clear division between true entrepreneurs and survivors. In the pre-crisis context, primarily, and the post-crisis period, secondarily, many respondents were considered true entrepreneurs, seeking business growth and perceiving relocation as an entrepreneurial opportunity for market expansion and cheaper production. These businesspeople own strong and productive firms and relocated to reach better profit opportunities. Apart from the relocation decision, the owners of these enterprises, which are mainly medium-sized, made important internal changes, such as development of new products, aiming at quality upgrade. Their operations in Bulgaria appear to be long-term, while several businesspeople reported that they would have relocated even if the crisis had not unfolded.

Since 2007, the Greek true entrepreneurs in Bulgaria have declined and most businesspeople are close to the profile of the survivor: owners of weak, small, and unproductive firms relocating to avoid business failure. Many entrepreneurs moved to Bulgaria as a reactive, unconsidered decision with no intention of making internal changes, seeking solely firm survival, and overlooking quality improvement. Thus, the change of firm location has not had a considerable impact on their business performance. This finding enriches the business mobility literature, which refers primarily to well-planned relocation decisions within a broader strategy of long-term investment to boost business competitiveness (Wilkinson et al. 2001; Zahra and George 2002; Smallbone et al. 2012). These survivor business tactics are related to the main characteristics of the Greek entrepreneurial mentality, including short-termism, unsound business strategy for making quick profits and low business expectations. Many survivors believed that relocation would solve all their problems, while continuing to focus on the Greek market, despite the substantial drop in demand. Their business operations in Bulgaria are not considered long-term.

On the other side of the border, Bulgaria provided a socio-economic context in which entrepreneurs could potentially sustain their business. In the neighboring country, Greek businesspeople drastically reduced operational cost as a result of the lowest corporate tax rate and labor cost in the EU alongside the Bulgarian institutions, which exhibit a modest level of development. Therefore, many businesspeople managed to improve the business performance, especially the true entrepreneurs, who have long-term business plans and proceeded with changes which are internal to the firm, such as the integration into new market networks and the introduction of innovation. Most survivors neglected such business tactics. Many of them failed in Bulgaria as they assumed relocation would solve all their problems. However, changes internal to the firm were essential, as they greatly influence, alongside the external socio-economic environment, business competitiveness (Krugman 1996; Bristow 2005). The overall moderate performance of Greek SMEs in Bulgaria has entailed a greater negative impact on the Greek regions, where these firms used to be located, than the positive effects on the Bulgarian regions, where these enterprises relocated.

Turning to policy recommendations, the results highlight the failure of the Greek government austerity policies to provide stable business conditions. These policies have focused on an internal devaluation through a great reduction of labor cost which, according to the narrative of the governors, would attract FDI in the country. However, this has led to deeper socio-economic inequalities (Giannitsis 2013). Furthermore, these policies have not been effective. Despite the great reduction of labor cost, inward FDI has not increased (Eurostat). On the contrary, thousands of businesspeople have relocated from Greece, as their enterprises’ operations were not profitable because of the significant deterioration of the wider economic and institutional environment. Progressive transformations, including the upgrade of production, the rise of wages and the improvement of institutional capacity, are necessary for strengthening the SMEs, which would boost employment, and for creating a more sustainable and socially just developmental model.

Departing from the findings and interpretations of this paper, particular priorities for future research agenda in economic geography are recommended. The hypothesis that is generated and needs to be tested in other cases is the following: owners of, mainly, weak firms in territories that are deeply affected by the economic crisis, like the EU peripheral economies, perceive relocation as a necessity to avoid business failure. For instance, the post-crisis increase of relocation of Italian firms to Romania needs to be further examined. Scholars could also test this hypothesis in other territories which have been greatly affected by the crisis, such as Spain and Portugal. The broader lesson for scholars examining business relocation and internationalization (Zahra and George 2002; Wright et al. 2007; Smallbone et al. 2012) is that apart from the change in the external socio-economic conditions, specific attention needs to be paid to the type of entrepreneurs who move. The motivations of the businesspeople, the incentives to relocate and the features of the firms should be considered. This is of great importance particularly for small- and medium-sized enterprises, whose performance is significantly affected by their owners’ tactics and mentality (Greenhalg 2008). Indeed, digging into the firms and considering their characteristics can provide valuable insights for business tactics and add to the explanation of relocation and its effects on business performance.

Notes

Enterprises that employ up to 250 employees and have an annual turnover of less than €50 million (European Commission 2003).

References

Alberti, F. (2006). The decline of the industrial district of Como: Recession, relocation or reconversion? Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 18(6), 473–501.

Arauzo-Carod, J.-M., Liviano-Solis, D., & Manjón-Antolín, M. (2010). Empirical studies in Industrial location: An assessment of their methods and results. Journal of Regional Science, 50(3), 685–711.

Arauzo-Carod, J.-M., & Manjón-Antolín, M. (2004). Firm size and geographical aggregation: An empirical appraisal in industrial location. Small Business Economics, 22(3–4), 299–312.

Aspelund, A., & Butsko, V. (2010). Small and middle-sized enterprises’ offshoring production: A study of firm decisions and consequences. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 101(3), 262–275.