Three Is a Crowd? Podemos, Ciudadanos, and Vox: The End of Bipartisanship in Spain

- 1European and International Studies, King’s College London, London, United Kingdom

- 2Department of Political Science and International Relations, Autonomous University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain

The traditional Spanish imperfect bipartisanship and the alternation in power that emerged in the early 80s between the center-left PSOE and the conservative PP have shifted towards a multiparty system after the emergence of three new parties. At first, as a result of the economic and political representation crises, Podemos (We Can) emerged at the 2014 European Parliament elections. This left-wing populist party managed to grow rapidly among the dissatisfied voters, reaching the third electoral position in the 2015 general elections. In the same contest, the liberal center party Ciudadanos (Citizens) became the fourth political force boosted, among other reasons, by notorious corruption scandals involving high-rank PP’s officials and the process of secession in Catalonia. Finally, driven by the same secession process and thanks to the removal from the office of PP’s Prime Minister after a motion of no confidence, the support for the populist radical right Vox also experienced a boost, winning 15 percent of the seats in Parliament in the general elections of November 2019. In this research, we describe the contexts which facilitated the irruptions of these new parties, analyze their impact on the Spanish party system, and study their current voters’ profiles.

Introduction

The success stories of Ciudadanos (Citizens) (Cs), Podemos (We Can), and Vox in the last seven years are good examples of the emergence of new parties after the Great Recession in Europe. Some of the most vivid and recent examples of these breakthroughs have been the Movimento Cinque Stelle (5 Star Movement) in Italy (born in 2013), La République En Marche (The Republic on the Move) in France (born in 2016), or Alternative for Germany (AfD) (born in 2013); all of them are able to play both the government and opposition roles in their respective countries.

After the Great Recession, the scenario of once stable social anchors as well as political and ideological alignments that hitherto explained vote choice needs to be (again) reconsidered in all European countries as their party systems appear to have entered a critical juncture, as Hooghe and Marks (2018) argue. The outcome is a reconfiguration of the European party systems with new party alternatives emerging and older ones losing voter’s support (Casal-Bértoa and Enyedi, 2016). The rising party fragmentation and electoral volatility suggest that the process of deinstitutionalisation of the European party systems has intensified during the last few years (Casal Bértoa and Weber, 2019; Hutter and Kriesi, 2019; Lisi, 2019). In most of the European countries, Spain is not an exception, new parties emerged challenging the traditional partisan and ideological loyalties.

With the emergence of new political forces, the generational change, and the electoral dealignment process, the transformation of the Spanish party system and the changes in the electoral bases of the main political parties should be studied in a thorough way. Thus, the goal of this article is fourfold. Firstly, in the literature review section, we underline the traditional institutional and contextual explanations to understand the emergence of new parties in Spain, exploring the institutional, economic, and sociological approaches, as all these factors matter to comprehend the emergence of Ciudadanos, Podemos, and Vox.

Secondly, we illustrate the changes introduced in the Spanish party system by the emergence of these new parties. In this section, we go back as far as the 1977 first Spanish democratic elections and finish the longitudinal analysis with the November 2019 general elections, focusing on three key characteristics of party systems: electoral fragmentation, electoral volatility, and polarization. We implement these analyses following previous works, such as the one of Rodríguez-Teruel et al. (2019), where the authors analyze this very same dimensions plus the dynamics of government formation, the cleavage structure—with a special focus in new dimensions of competition that emerged after the Great Recession—and the party system institutionalization.

Thirdly, and in a party-by-party strategy, we analyze the specific main drivers of the new Spanish political forces. Data from the Spanish Center for Sociological Research (Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas—CIS) are used to show how the evolution of certain attitudes and issue salience (i.e., political discontent, economic grievances, corruption, and Catalan independence) paved the way for the rise of these challenger parties.

Finally, we test to what extent the main explanations that have helped to explain the success of Podemos and Ciudadanos in 2015, and Vox in April 2019, are still valid for describing their voter bases with more recent data (postelectoral data from the November 2019 elections). Entering the electoral arena is one thing, but maintaining support is another. We discuss how that the faith of these new parties might depend on whether their voters are sufficiently distinct from the voters of other parties on the key dimensions that allowed for their breakthroughs in the first place.

Our main argument is that, while more proportional second-order (regional and European) elections opened the door for the entrance of these Spanish new parties, the truth is that both political (corruption scandals, the crisis of traditional parties, and the Catalan secession process and the consequent territorial crisis) as well as sociological factors (age and education) play a fundamental role for understanding the recent emergence of new parties in Spain, with the cultural issues (gender and migration), playing a more secondary role.

Why New Parties? The Combination of Institutional and Contextual Factors in Spain

Research on new parties has traditionally identified three main sets of explanations on this regard: institutional (Hauss and Rayside, 1978; Bolin, 2007; Hino, 2012; Lago, 2021), sociological (Harmel and Robertson, 1985), and economic ones (Pinard, 1971; Tavits, 2007). In this section, we briefly explain how each one applies to the recent evolution of Spanish party system.

Institutional Explanations

On the institutional side of the explanation, it has been well established that the emergence of new parties is more likely in countries with more proportional electoral systems (e.g., Netherlands) than in countries with majoritarian ones (e.g., United Kingdom). Although almost every electoral contest witnesses the birth of new parties across Europe, most of these “new-born parties” do not succeed in obtaining parliamentary representation. Bolin (2007) shows that the electoral system is the key factor for understanding the success of new political options, finding a positive relationship between the size of the Parliament and the size of the district magnitude with the probability of a new party emergence. Together with the electoral system, the type of elections matters for the breakthrough of a new party. It is well known that second order elections (Reif and Schmitt, 1980), such as the European Parliament (EP) ones, boost the support for nonmainstream parties and increase the probability of a new party to emerge. More recently, Schulte-Cloos (2018) has applied this hypothesis to populist radical right parties, while Lindstam (2019) has focused on how more general niche parties gain ground in EP elections (Farrer, 2015).

Both explanations fit well the Spanish case. In this sense, it is well known that the electoral system for the parliamentary elections is quite restrictive in allowing new parties to obtain seats in Congress. Despite not being a majoritarian system, the combination of a big number of districts (52 provinces) with varying magnitudes (ranging from 37 to 1 seat) to distribute 350 seats at the Congress and the application of the D’Hondt method to transform the votes into seats has traditionally generated a majoritarian bias, hindering the representation of small parties at the national level. While the two main parties at each district obtain a better representation [mainly the conservative People’s Party (Partido Popular, PP) and the social democrat Spanish Socialist Worker’s Party (Partido Socialista Obrero Español, PSOE) and also the nationalist and regionalist parties], third state-wide parties such as the left-wing coalition United Left (Izquierda Unida, IU) as well as Union Progress and Democracy (Unión Progreso y Democracia, UPyD) used to secure parliamentary representations far below their electoral support. In fact, the percentage of Congress’ seats obtained by the sum of PP and PSOE was 85% in 2011 and 92% in 2008.

The majoritarian bias of the electoral system in the general elections in Spain explains why successful new parties debut in less restrictive contests to gain electoral support and visibility. Not in vain, in recent years Ciudadanos and Podemos’s national-level breakthroughs took place at the European Parliament (EP) elections of 2014 (Cordero and Montero, 2015) with single district and therefore a proportional method of access. Of course, these elections are second order ones (Reif and Schmitt, 1980), in which voters tend to punish big parties and not vote strategically, usually benefitting smaller parties, but assuming this, second order elections represent the perfect first act scenario for new parties before they win sits in the general elections in Spain.

EP elections allow new parties to gain country-wide visibility and to compete in subsequent first order elections perceived as viable alternatives by the electorate. In fact, after showing promising results in the polls, Podemos and Ciudadanos combined achieved more than a third of the votes in the 2015 general elections, winning 109 out of 350 seats in the Congress (Orriols and Cordero, 2016; Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio, 2016), with PP and PSOE maintaining only 61% of the seats. Interestingly, this first electoral earthquake was followed in April 2019 by a seaquake, with the success of another new challenger party: the populist radical right Vox (Turnbull Dugarte et al., 2020), which obtained over 10% of the vote, putting an end of the Spanish exceptionalism as a country free of successful radical right parties (Alonso and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2015). In contrast to the other two newcomers, Vox did not succeed in obtaining seats in the EP elections of 2014. For Vox, it was not until the 2018 regional elections in Andalusia (also a second order one, with a proportional system) that it gained enough visibility and feasibility to win seats in general elections. In the snap November 2019 general elections, Vox became the third party in terms of electoral support and number of seats (15% of the votes and 52 out of 350 seats in the Congress).

Contextual (Social and Economic) Explanations

However, the characteristics of the electoral system and their more proportional nature are not the only factors behind the success of new political parties (Mainwaring and Torcal, 2006). On the social side, the increase in relevance of new dimensions of political competition able to substitute or to be added to the established ones has been found to be a key factor explaining the emergence of new parties (Green-Pedersen, 2010; Ford and Jennings, 2020). This is the case, for instance, of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), which clearly grew as a niche party with an owned issue: the European Union membership referendum. In Spain, the presence of new political issues combined with the lack of political supply to meet the corresponding demands of the electorate is also key to the success of new challengers (Lago and Martínez i Coma, 2011). In this sense, as we will discuss in the following sections, there are three main explanations to why Ciudadanos, Podemos, and Vox have emerged successfully. In short, while the Great Recession and the great political discontent it generated are behind the emergence of Podemos (Cordero and Simón, 2015; Bosch and Durán, 2019), it is the corruption scandals of the traditional right (PP) since 2012 and the secession process in Catalonia since 2017 that help to explain the rise of Ciudadanos (Cordero and Montero, 2015; Orriols and Cordero, 2016). For the case of Vox, the Catalan issue and the federalist tensions inherent to the Spanish decentralized system and the concerns over immigration are the main drivers to understand its success (Turnbull Dugarte et al., 2020; Rama et al., 2021).

Finally, economic factors have been identified as one leitmotif of explanations of the emergence of political parties (Morlino and Raniolo, 2017). This was the case of the Social Credit Party of Canada, which clearly emerged as a response to the high levels of unemployment (Pinard, 1971). In fact, Tavits (2007: 118) penned that “perhaps the most consistent result from the studies of party emergence in advanced democracies is the effect of short-term economic performance”. In this sense, there is a broader consensus on how economic recession increases entries of new political parties, as it provides new party elites with an opportunity to profit from the economic policy failures of the existing parties and especially the incumbents. However, with the exception of the appearance of the liberal UPyD in 2008, Spain had been a country free of (successful) new national political parties since the early eighties, and although the economy experienced abrupt ups and downs since the establishment of democracy in the 1970s, it did not translate into the emergence of new parties. In this regard, traditional forces (PSOE and PP) managed to absorb economic shocks and resulting societal discontent through alternating power.

Nonetheless, the context of the Great Recession and the resulting social unrest and political instability has been particularly fertile for the appearance of new parties especially in Western (Kotroyannos et al., 2018; Vidal, 2018) and in some Southern European countries (Morlino and Raniolo, 2017). The economic and social consequences of the Great Recession are behind the success of new parties also in Spain, being an especially relevant explaining factor for Podemos. The social protests against spending cuts linked to the 15-M Anti-Austerity Movement are in the roots of this achievement, although the demand for “Real Democracy” and the disenchantment with politics at a time of deep recession and social grievances are the main reason behind its rapid growth (Portos, 2020).

The Spanish Party System: The Calm Before the Storm

To understand the metamorphosis of the Spanish political system, it is essential to understand how it has evolved over recent decades. Whereas the electoral cycle that started in 2015 could be described as turbulent (Lagares et al., 2019; Méndez, 2020) and certainly as elections of the final cycle of a great crisis (Llera et al., 2018), the history of the Spanish party system after 1977 is better characterized by its stability. In this regard, there is certain consensus on the characterization of four electoral cycles in Spain’s recent history, each one of them defined by different levels of fragmentation, patterns of competition among parties, and polarization (Montero, 1988; Linz and Montero, 2001; Rodríguez-Teruel, 2021). The first one, the foundational elections cycle, comprises the first two democratic elections after the restoration of democracy: 1977 and 1979. These foundational elections resulted in a moderate pluralist party system. Adolfo Suárez’s center-right Union of the Democratic Center (Unión de Centro Democrático, UCD) comfortably won the 1977 elections and led a minority single-party government whose main task was to deliver a democratic Constitution (Montero and Lago, 2010). In the 1979 elections, UCD revalidated its victory, establishing a second single-party minority government. However, due to several factors, including a complicated economic situation and disagreements within the governing party, Suárez resigned.

The second cycle, the democratic consolidation, encompasses four elections: 1982, 1986, 1989, and 1993. During this cycle, marked by the political hegemony of Felipe Gonzalez’s social-democrat PSOE, the relevant milestones were three: 1) the critical 1982 elections meant the UCD collapse (from 168 to 11 seats in the Congress), 2) the PSOE boomed (from 121 to 202 seats), and 3) the conservative Alianza Popular (AP), the predecessor of the PP, emerged as the main opposition party (from 9 to 107 seats). In the subsequent elections (1986 and 1989), González concatenated two absolute majorities of seats and a final simple majority in 1993.

The third cycle is characterized by an extraordinary intensification of the electoral competition between PSOE and PP, as well as the alternation in power between these two parties. It covers five elections: 1996 (minority government of José María Aznar’s PP), 2000 (majority government of Aznar), 2004 and 2008 (minority governments of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero’s PSOE), and 2011 (majority government of Mariano Rajoy’s PP). Interestingly enough, in the three elections resulting in simple majorities, the winner party had to gather the support of regionalist and nationalist parties to become invested and seize government, although in none of these occasions did this backing translate into a coalition government.

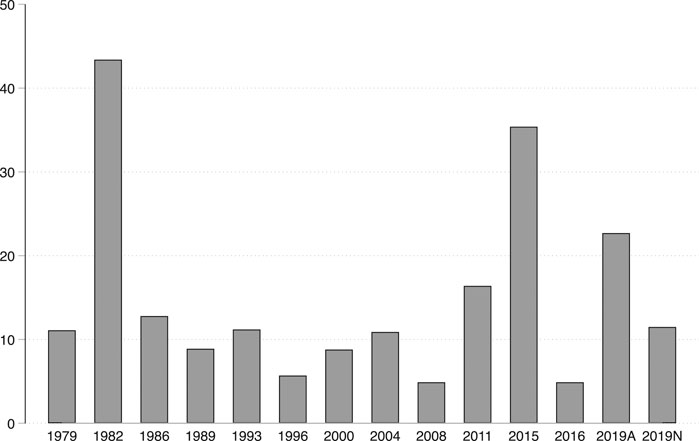

The fourth cycle opened a new scenario of political instability. The electoral earthquake of the 2015 general elections (with more than 35 percent of volatility—Figure 11—, only comparable to the one experienced in 1982 due to the collapse of the ruling party UCD) posed a sharp cut in the combined share of the PP and PSOE votes (down to 51.1 percent in 2015 from 74.4 in 2011) and seats (60.9 from 84.6), sending the smaller parties United Left [Izquierda Unida (IU)] and UPyD to the morgue, bringing as well the irruption of two new relevant national players: Podemos (with more than 5 million votes and 69 out of the 350 seats) and Ciudadanos (3.5 million votes and 40 seats). The combination of a balanced distribution of seats in each ideological block (PP and Ciudadanos gathered 163 seats, while PSOE and Podemos 159) and the difficulty of obtaining enough support from regionalist and nationalist parties precluded the formation of any government.

FIGURE 1. Electoral volatility in Spain, 1979–2019. Source: Own elaboration based on Rama et al. (2021).

Thus, new elections were called for on June 20, 2016. Again, the distribution of votes was similar for both ideological blocks, but this time the PP reached enough support to form a Government, only after the resignation of PSOE’s leader, Pedro Sánchez. Mariano Rajoy was able to set up the government with the lowest share of seats (only 39.1 percent) since 1977. Less than two years later, in June 2018, the PSOE—boosted by the corruption scandals of the PP and after the comeback of Pedro Sánchez as the party leader—rallied opposition parties to bring the government down in a censure vote. The ensuing PSOE government depended on the support of United We Can (Unidos Podemos) (UP)2 and the external support of nationalist and regionalist parties. After the Catalan parties had refused to back the government’s budget bill in February 2019, early elections were called.

The April 2019 general elections brought a big winner, the PSOE, and the big loser, the PP (from 137 seats in 2016 to just 66 seats in April 2019), partly because of the growth of Ciudadanos (from 32 to 57 seats) and partly due to the entrance of a new radical right party: Vox (with 24 seats). Far from being the end of turbulent times, the lack of agreement between PSOE and UP led to new elections in November 2019, which gave place to an even more fragmented parliament, in which the PSOE resulted in the winner again, and Vox ascended to the third position, reaching unprecedented digits: 3.6 million votes, 52 out of 350 seats in the Congress and 15.1 percent of the votes. This election meant the collapse of Ciudadanos (loosing 47 seats) and the PP’s revival (regaining 23 seats).

Figure 2 displays the trends of electoral fragmentation (index of Effective Number of Electoral Parties (Laakso and Taagepera, 1979)3, accounting for the variations in terms of political instability and the consequent difficulties of government formation since the instauration of democracy in 1977. The pattern is clear: from a hegemonic party system for the 1982–89 period (with the dominance of PSOE) to a two-party plus system in the 1993–2011 period (with the alternation of government between the almost equally strong PSOE and PP) and a final fragmented (and polarized) period since 2015, with four major national parties (PSOE, PP, Podemos, and Ciudadanos) which, after the April 2019 elections, became five, given the rise of Vox.

FIGURE 2. Effective number of electoral parties, 1977–2019. Source: Own elaboration based on Rama et al. (2021).

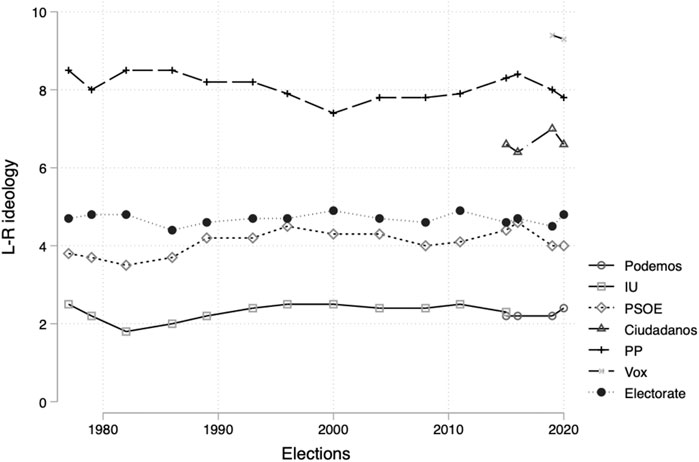

These changes in the format of the party system towards a more unstable and fragmented one were complemented with ideological changes from the political parties’ side. Figure 3 displays the aggregate levels of ideological placement of the main national parties from 1977 to 2019 by the electorate. From 1977 to 2011, the competition on the ideological scale is well defined, with IU and PP occupying the extremes—IU between 1.8 and 2.5, and PP between 7.4 and 8.5 on a scale from 1 (Left) to 10 (Right). Since 2015, the extreme left space has become occupied by Podemos, whereas in 2019, Vox replaced the PP at the extreme right. In the last years, we find interesting flows in the perception of some political parties by the electorate. Especially interesting are the cases of PP and Ciudadanos. The liberal party moves from 6.4 in 2016 to 7 in April 2019, whereas the conservative PP was able to “come to the center” with the emergence of Vox, moving from 8.4 in 2016 to 8 in April 2019 and 7.8 in the November elections (a change of 0.6 points in just 3 years). All in all, comparing the extreme points of Figure 3 in the 2000s and in last elections, it is fair to say that polarization has grown significantly—although the electorate’s placement (see the black circle points in Figure 3) have not changed significantly, as the average since 1977 to November 2019 is 4.7 and the standard deviation in these fifteen elections is only 0.14 points (Rodríguez-Teruel, 2021).

FIGURE 3. Political parties and voters in the ideological left-right scale, 1977–2020. Source: Own elaboration based on postelectoral data from Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS).

What Happened? Explaining the Rise of Podemos, Ciudadanos, and Vox

Podemos

The electoral success of Podemos and other left-wing populist parties such as the Coalition of the Radical Left (SYRIZA) in Greece or the emergence of La France Insoumise (Rebellious France) is among the indirect political consequences of the Great Recession in Europe (Armingeon and Guthmann, 2013; Fernández-Villaverde et al., 2013; Gougou and Persico, 2017). This success has been linked to a critical view by the electorate on the consequences of the economic crisis (Fraile and Lewis-Beck, 2012; Bellucci, 2014; Magalhães, 2014), which has been at the root of erosion of trust in the institutions and traditional parties. Podemos grew up from the heat of the social movements linked to the Anti-Austerity 15-M Movement in Spain (also known as the Indignados Movement) and the disenchantment with politics at a time of deep recession, relative deprivation and social grievances (Portos, 2020). This situation brought people’s confidence in the traditional parties (already very low even before the Great Recession) down and deeply eroded their satisfaction with the political system (Cordero and Simón, 2015).

Despite the fact that numerous mobilizations against social spending cuts and economic intervention, calling for mechanisms of direct democracy (one of the main organizers was “Democracia Real Ya”, Real Democracy Now) spread across Spain already in spring of 2011, it was not until early 2014 that Podemos managed to canalize this discontent, standing for the EP elections, as no relevant elections took place in the 2011–2014 period. In this contest, in which the polls did not anticipate any representation for this recently created party, Podemos reached the 8% of the votes, winning 5 of the 54 seats at stake. By doing so, Podemos, a party born just four months before the elections, became the great surprise of the contest by emerging as the fourth Spanish party in the European Parliament (Cordero and Christmann, 2018). As discussed above, the success of Podemos in this contest was possible thanks to the permissive electoral system of the EP in Spain: a single district to select 54 seats allowed Podemos to reach the proportional results that the Spanish party system would have prevented.

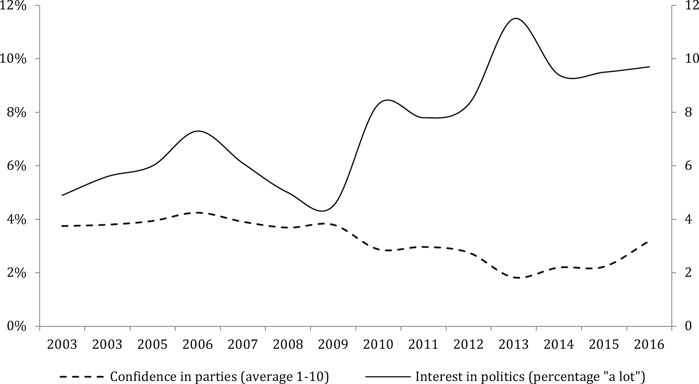

However, on top of the institutional setting that made the emergence of a successful new party possible, Podemos owes its popularity to a populist discourse based on the dichotomy between “the caste” (la casta) and “the people”. This discourse went beyond the traditional critics towards the two main parties PP and PSOE, censoring the economic and media powers, political institutions, and the “public powers” understood in a very broad way. It resonated particularly well with the disaffected electorate who witnessed the incapacity of “the political class” to manage the economic and social repercussions of the crisis (Torreblanca, 2015). Now, although political disaffection has traditionally encompassed both high levels of mistrust in institutions and disinterest in politics (Torcal and Montero, 2006), only the former characterized the Spanish electorate during the Great Recession. As shown in Figure 4, the average confidence in parties, already very low before the Great Recession, reached critical levels between 2013 and 2014. This evolution mirrors the trend of people’s interest in politics. Although at the beginning of the crisis only 4% of citizens were “very interested” in politics, during the worst years of the crisis, this percentage surpassed 10% (it goes from 28 to 39% between 2007 and 2014 when adding those who are “very” and “quite” interested in politics). It is within this context that Podemos found its electoral potential base for the 2014 EP elections: left-wing voters with low levels of satisfaction with democracy and extremely low levels of trust in the institutions and traditional parties (Cordero and Montero, 2015).

FIGURE 4. Average confidence in parties (0–10) and percentage of people with “a lot of interest” in politics in Spain, 2003–2016. Source: Barometers of the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS).

Thus, the combination of high levels of mistrust in political and economic institutions, the perception of broken promises by the mainstream parties, the opposition to social expenditure cuts and increasing levels of interest in politics gave rise to a critical electorate, which responded by mobilizing massively in the streets (Medina, 2015) and supporting a recently created party, openly opposed to “la casta”, in their own terminology, embodied also by the austerity-imposing elites in Brussels and Madrid (Cordero and Simón, 2015; Torcal, 2017). This discourse was widely broadcasted by its leader, Pablo Iglesias, in some of the major television networks in Spain right before and during the EP elections (Torreblanca, 2015).

But the 2014 EP elections were only the first context where Podemos showed their viability to become a serious threat to the traditional two-party system in Spain. In March 2015, Podemos obtained 15% of the vote at the regional election in Andalusia (the most populated region in Spain), and two months later the candidates of left-wing formations close to Podemos became the majors of the two first Spanish cities (Madrid and Barcelona) at the May local elections. However, the main question remained unresolved. Could a party about the size of Podemos overcome the restrictions of the Spanish electoral system for the National Parliament to obtain a fair representation, or would Podemos be hardly punished, as previous left-wing coalitions at the national level were? In December 2015, general elections were held with Podemos obtaining (together with other regional left-wing coalitions close to Podemos) an outstanding 20.7% of the votes to become the third parliamentary group with 65 seats, just after PP (119) and PSOE (89). The success of Podemos demonstrated that the Spanish electoral system allows for a third party to become a major player in the Parliament and that its majoritarian bias is reduced in a more fragmented and competitive context.

Since then, although it aimed for a sorpasso of PSOE as the leading party on the left, Podemos has remained the second left-wing force. At the 2016 general elections, Podemos led a coalition of left-wing parties, absorbing the traditional United Left, forming United We Can (Unidos Podemos). After the 2019 elections, Unidas Podemos became the junior partner of PSOE in the first coalition government in the recent history of Spain in which its leader Pablo Iglesias was appointed vice-president. After entering the government, Podemos has followed a pattern of institutionalization and depolarization, though tensions between the coalition partners are constant. At the time of this writing, the polls predict certain electoral stability for Unidas Podemos in the short term, with a relevant change in its electoral prospects being relatively unlikely also at the medium term. Even considering the fact that junior coalition partners are usually penalized in subsequent elections (although there is some discussion, Klüver and Spoon, 2020), and the replacement of Pablo Iglesias as party leader, Podemos rather than being a flash party seems to have established itself as one of the key players in the Spanish party system in just few years since its creation.

Ciudadanos

Established in Catalonia in 2006, Ciudadanos had to wait until the EP elections of 2014 for its first electoral breakthrough outside of the region, obtaining 3.2% of the votes and securing 2 seats. Although this was conceived as a good result for the party, the rapid growth of Ciudadanos did not begin until several months later. As discussed before, probably the most remarkable feature of the 2011–2015 period and the main reasons behind the boost experienced by Ciudadanos are the comprised cases of corruption affecting the conservative party in Government, the PP. Just to mention some examples, the “Black Cards” case, in which the savings bank Caja Madrid—Madrid’s regional government-owned bank (Huffington Post, 2014; Águeda, 2014; Orriols and Cordero, 2016)—was investigated for illegally using credit cards for personal purchases (Minder, 2014). This case ended in a trial against 86 members of the board of directors, most of whom had been nominated by political parties and trade unions. Rodrigo Rato, the bank’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO), former Minister of Finance and Economy and former Head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), was sentenced to six years in prison for this case.

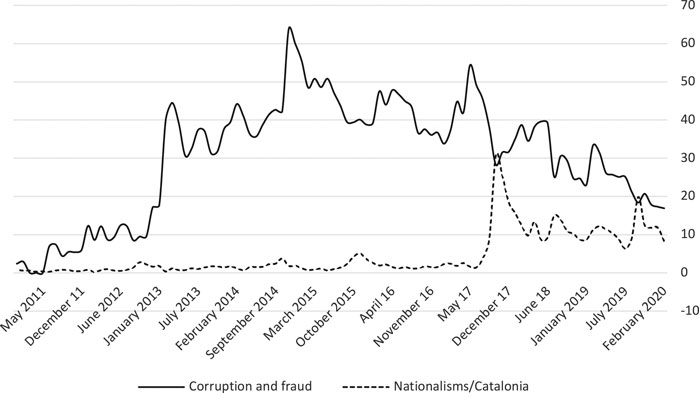

However, the so-called Gürtel affair, in which some PP members received bribes in exchange for public contracts, was the most impactful case of corruption (Manetto and Cué, 2013; Fortes and Urquizu, 2015; Fernández-Vázquez et al., 2016; Cordero and Blais, 2017). This scandal dates back to 2009, although the details of the case were revealed during early 2013, resulting in a peak in corruption salience as one of the main social concerns for the first time since the beginning of the Great Recession. Since then, corruption has been one of the most significant concerns in Spain for around half of the respondents in the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS) monthly barometers (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5. Percentage of population that perceives “Corruption/fraud” and “Catalonia/nationalisms” as one of the three main concerns in Spain (May 2011-February 2020). Source: Barometers of the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS).

Due to these relevant and sizable corruption scandals, front-line PP members resigned. According to the judiciary, the PP operated “a financial and accounting structure that ran parallel to the official one, at least since 1989”. This series of events, with the disclosure of more details of the case resulted in the second peak of the trend in October 2014, when only in one region, the Valencian Community, a total of 141 PP party members were investigated (Pardo, 2013)4. Ciudadanos presented itself as an example of democratic regeneration and a guarantee of fight against the traditional parties’ corruption (Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio, 2016). As a characteristic shared with Podemos, a party was also built on challenging the status quo, democratic regeneration, and the denouncement of corruption.

However, as shown in Figure 5, nationalisms and the demands of independence in Catalonia, commonly known as the procés, were also among the main political issues during the period, peaking as the main concern for the Spanish citizens in October 2017, coinciding with the referendum on Catalan independence. The procés itself was the consequence of a series of developments that were set in motion at the beginning of the 2010s. Facing several judicial trials because of large political corruption scandals, Convergence and Union (Convergència i Unió, CiU), headed by its new leader Artur Mas, embarked Catalan nationalists on a series of anticonstitutional activities, including an unauthorized unilateral consultation in 2014, the proclamation of a so-called rupture or transitional law by the regional parliament in September 2017, and the holding of a second unauthorized plebiscite (Montero and Santana, 2020).

On the 1st of October, the Catalan government organized a referendum on the region’s independence from Spain, which the Spanish government and the Constitutional Court considered illegal. Over two million Catalans (43% of eligible voters) participated in the vote and over 90% voted in favor of the independence. Mariano Rajoy’s government sent riot police and, as a result, the Catalan Healthcare Service reported that over 1,000 patients were injured by the police charges, according to the Catalan Health Service (Benito, 2017). The role of the Government during this crisis was heavily criticized from both sides. While some actors censured that the Spanish Government was not able to prevent the referendum to take place, others condemned the brutality of the public security forces employed for closing the polling stations across Catalonia. In this, Ciudadanos highlighted its firm position against the secession, advocating for heavy-handed measures against the proindependence parties. Thanks to this series of events, Ciudadanos was strengthened, as the polls predicted an increase of 6% of the estimated vote for general elections in just six months (from 14.5% in July 2017 to 20.7% in January 2018, according to the CIS barometers).

Nearly a month after the referendum, on 27 October, the Parliament of Catalonia unilaterally declared Catalonia an independent state and the PP government subsequently invoked Article 155 of the Spanish Constitution to suspend Catalan autonomy. Following this declaration, the former President of the Catalan Government, Carles Puigdemont, and some of his cabinet fled from the country, while others (including Oriol Junqueras, the former Vice-President) were detained. As a consequence, the Spanish government called an election to the Catalan Parliament. Ciudadanos won the election with unprecedented results, obtaining one out of four votes in the region, but prosecessionists obtained another majority of seats, although not votes (Martí and Cetrá 2016; Orriols and Rodon 2016; Guntermann et al., 2018), selecting another proindependence regional Prime Minister.

The success of Ciudadanos is closely linked to public concern over corruption and the secession in Catalonia, as the evolution of support for the party peaks in line with corruption and nationalisms salience. The Ciudadanos’ voter profile matches this explanation (Orriols and Cordero, 2016). In the regional elections between 2015 and 2018, Ciudadanos started to score double-digit shares of the votes, becoming part of important regional governments, such as Andalusia and Madrid, and winning in Catalonia (the first, third, and second most populated regions in Spain, respectively). In the general elections of 2015, Ciudadanos obtained 14% of the vote and 40 seats, mainly at the expense of the PP, which lost 3.7 million votes and 63 seats since last general elections. In comparison to the PP voter, the Ciudadanos’ voter was younger and closer to the ideological center. However, two of the most determinant aspects explaining the support for Ciudadanos were their higher levels of concern about political corruption and lower levels of trust in politics than the traditional PP voter (Orriols and Cordero, 2016). According to CIUPANEL data (Torcal et al., 2016), 14% of the PP electorate in 2011 voted for Ciudadanos in 2015.

Ciudadanos continued its ascend for some time, obtaining good electoral results in the general elections of 2016. Despite being conceived as a center liberal party able to reach agreements with the two main parties in pursuit of democratic regeneration, Ciudadanos chose to back PP candidates in all the regions where the PP obtained simple majorities after the 2015 elections. These agreements were reached also in regions where the PP had been governing for decades and where the cases of corruption were more widespread, such as Madrid and Murcia. Ciudadanos also voted against the motion of censure that removed Mariano Rajoy from office due to corruption scandals in 2018. Despite this, in the subsequent April 2019 elections, Ciudadanos reached their best electoral results in a national contest, obtaining 57 seats.

However, the Ciudadanos’ campaign of veto on PSOE and a marked right turn reduced its electoral prospects for the November 2019 elections. Additionally, Ciudadanos’ heavy-handed approach against the secessionism did not result in the end of the polarization of Catalan politics nor did it tip the balance for the nonsecessionist side of the conflict. All these movements might be behind the drastic reduction of Ciudadanos’ popular support, lacking their perceived capacity to be a guarantor of democratic regeneration as a hinge party nor the solution to the Catalan conflict (Figures 3, 5, respectively). In fact, in the 2019 general elections, Citizens went from 4.2 million votes (57 seats) in April 2019 to 1.7 million votes (10 seats) in just six months. In the 2021 Catalan elections, the region where the party was born and where it has traditionally obtained its best results with a clear antisecessionist message, Ciudadanos went from 36 seats in 2017 (first political force) to only six seats (seventh political force). Today the polls still predict poor results for Ciudadanos and its new leader, putting at risk the very survival of the party as a relevant actor in the medium term at the regional and, especially, at the national level.

Vox

The December 2018 regional elections in Andalusia marked a turning point in Spain’s democratic history with the unprecedented breakthrough of the populist radical right party Vox. Since it was born as a result of an internal split from the PP in 2013, Vox had survived five years with null electoral support. It participated in the EP elections for the first time in 2014 and received 1.6 percent of the vote, failing to gain any representation. In 2015, the party run for the first time in a national election, obtaining only 0.23% (58,114 votes) of the votes. Then, in the snap election of June 2016, the party’s electoral support decreased to 0.20% (47,182 votes).

If there is one issue that helps best to understand the emergence of Vox as successful competitor, it is the Catalan independence process, which gained momentum in 2017. As described before, the PP’s response to Catalan separatists’ unilateral declaration of independence in October 2017 was to invoke the Article 155 of the Constitution, which facilitated the dissolution of the regional government and the temporary rule over the region from Madrid. However, Mariano Rajoy’s government response, firstly, trying to avoid the participation in the unauthorized plebiscite by force, and secondly, applying the above-mentioned article 155, contributed to further polarization and heightened territorial tensions across the country (Simón, 2020; 2021). In fact and even more importantly, the late response of Government to the secessionist acts at least in the eyes of an important section of right-wing voters created political opportunity structure for Vox stepping in as a viable contender. Thanks to the role of a popular prosecutor against the leaders of the procés, Vox gained presence in the media and managed to present itself as the sole party defending the unity of Spain against Catalan independence movement a distorted picture, given that PP, Ciudadanos, PSOE, and even Podemos oppose Catalan secession. However, unlike theses parties, Vox does not defend the quasifederal structure of the “estado de autonomías” but advocates the permanent dissolution of Spain’s decentralized system and the consolidation of state power within a central (national) layer of government. Figure 6 shows that Vox supporters are significantly more likely than voters of other parties to declare that the Catalan conflict was a decisive factor influencing their vote choice.

FIGURE 6. Percentage of voters declaring that the issue of Catalan independence was decisive in their vote choice. Source: Own elaboration based on CIS, 2019a and CIS, 2019b.

The issue of Catalan independence and the defence of centralization efforts, together with a nationalist and antifeminist agenda, the criticism to mainstream media, characterized by the party as a “lying machine” that “crafts fake news from progressive bureaus of radios and televisions, which help to prop up the progressive dictatorship” (Ribera Payá and Díaz Martinez, 2020: 15), and the identification of immigrants as an external “threat” to the Spanish culture, allowed Vox to tension the electoral competition on the issues used also by other populist radical right parties worldwide and transform the party into a competitive electoral player in an ever more polarized context.

Additionally, by advocating a romanticized image of the past, Vox is shown to be sympathetic to predemocratic times, with constant allusions in their messages to a better past as well as to nostalgia of other allegedly glorious times. In this sense, although radical right parties are not against democracy per se (Mudde, 2019), the references to the “Living Spain” (España Viva) in opposition to the “Anti Spain” (Anti España) related to the general elections of 1936, a prelude to the civil war present both in the electoral manifestos and in the public speeches of the party’s leaders (Casals, 2020), point towards an at-best ambivalent view of Francoism (Martín et al., 2021).

Thus, in few years, Vox went from null representation to a kingmaker in Andalusia, Madrid, and other regions. Its role at the national level is limited, but future right-wing governments will most probably be dependent on its support and the PP gives signs of radical right mainstreaming. Along the way, Vox managed to distance itself from the social stigma of association with extremism due to its image of insider (as a splitter from the mainstream PP) and to campaigning on the issue of Catalan independence rather than on the issue of immigration (most widely shared by other populist radical right parties), which gave the party a “reputational shield” shifting the negative media coverage associated with previous radical right parties and movements to a more positive one (Mendes and Dennison, 2021). It succeeded to steal voters mostly from the PP, especially after the removal of PP’s Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy from office after the motion of no confidence, which, together with corruption scandals eroded the image of the PP, giving room to the party of Santiago Abascal to gain ground. Today, the polls predict electoral growth for this young party at both regional and national levels. Not in vain, in the 2021 Catalan elections, Vox became the fourth political party at the regional Parliament with 11 seats, ahead of the PP with only three seats (eighth party at the chamber).

Profiling the New Parties’ Voters

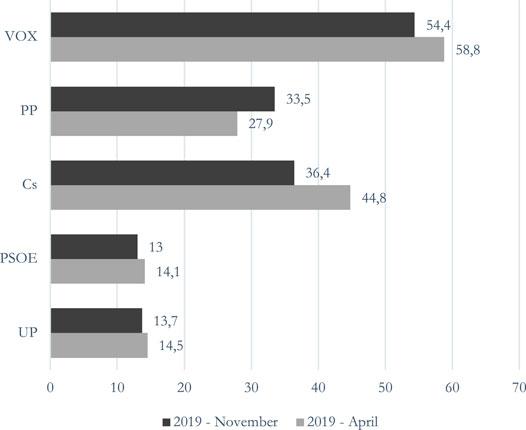

Until now, we have described how institutional setting and political opportunity structures allowed for the recent emergence of new parties in Spain. In what follows, we shift the focus to the demand-side specifically and study the sociodemographic and attitudinal profiles of voters of Podemos, Ciudadanos, and Vox once represented in the national parliaments. The questions we want to answer are as follows: do the explanations on the emergence of these new parties match their current voter profiles? Which individual-level factors distinguish voters of new parties from those of the traditional ones (PP and PSOE)? To answer them, we will compare vis à vis voters of Unidas Podemos to voters of PSOE, voters of Ciudadanos to voters of PP, and voters of Vox to voters of PP also5.

Building on the existing literature, in the first place, we expect that voters of all new parties (Podemos, Ciudadanos, and Vox) will be more likely to be younger, politically more dissatisfied, have higher interest in politics, and attribute more importance to corruption (Haughton and Deegan-Krause, 2020; Marcos-Marne et al., 2020). The assumption here is that younger, less satisfied, more interested, and more preoccupied with corruption citizens will be more likely to try a new party, because they are more likely to experiment with their vote, have lower party identification, be more informed about the corruption of the traditional parties, and search for alternatives, independently of their ideological profile (Dassonneville, 2013).

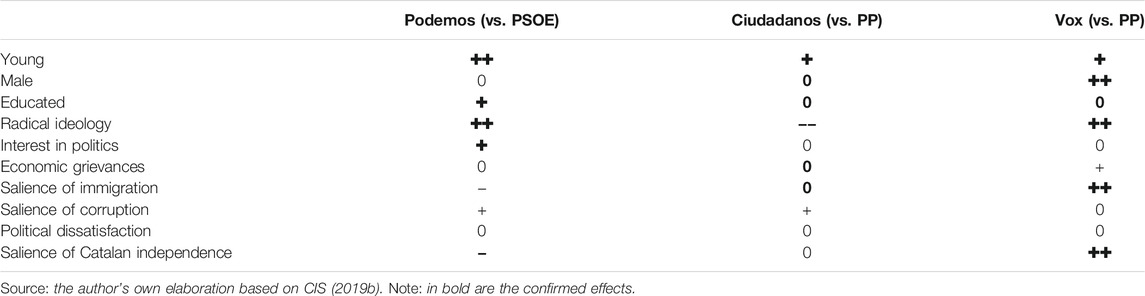

Second, with regard to Podemos and Vox, we expect that their voters will be more likely to place themselves further from the center of the ideological scale and to be male in comparison to the voters of PSOE and PP, respectively (Ramiro and Gomez, 2017; Rooduijn, 2018; Stockemer et al., 2018; Rama et al., 2021). Third, considering only the differences between voters of Podemos and PSOE, we anticipate Podemos’ voters to be better educated and more likely to express economic grievances (Orriols and Cordero, 2016; Bosch and Durán, 2019). In light of the extant empirical evidence, we do not expect Vox’s supporters to be more economically deprived than voters of PP (Turnbull-Dugarte et al., 2020). In line with the cultural backlash thesis (Norris and Inglehart, 2019), we hypothesize that Vox supporters will be more likely to be more concerned with the issue of immigration than voters of PP, while it will not be a divisive issue on the left. Lastly, we expect the voters of Vox and Ciudadanos to attribute higher salience to the Catalan issue, compared to PP’s supporters. Table 1 gathers the expected effects for each comparison at the voters’ level.

TABLE 1. Expected effects of individual level factors on voting for Podemos vs. PSOE, Vox vs. PP, and Ciudadanos vs. PP

We test for the hypothesized differences between voters of the new parties and voters of the traditional, mainstream ones, using data from the nationally representative sample of nearly 5,000 respondents of the CIS postelectoral survey carried out after the general elections of November 2019 (CIS, 2019b). Three dichotomic dependent variables—vote for UP (1) vs. PSOE (0), Cs (1) vs. PP (0), and Vox (1) vs. PP (0), always leaving aside voters of other parties, nonvoters, those not-knowing, not-answering, and null and blank votes—are used to carry out binary logistic regression models. Data are weighted and standard errors are robust.

The key independent variables are the following: age (6 categories), gender (1 = women), educational level (primary, secondary, and university), radical ideology (distance from the center of ideological scale in self-placement), interest in politics (4-point scale), egotropic evaluation of the economic situation (4-point scale), immigration issue salience, corruption issue salience, political disaffection, Catalonia independence issue salience (the last four variables are coded one if respondents declare the issue as one of the three most pressing concerns for the country; political disaffection is measured by “politicians” being one of the main concerns), and the effect of the Catalonia independence issue on vote choice. We operationalize the Catalan independence issue through two variables given that expressing concern about it does not necessarily translate into it being a decisive factor for the vote choice6. Supplementary Appendix S1 in the Online Appendix gathers the descriptive statistics of all variables. We also include dummies for Spanish regions to account for the interregional party system differences.

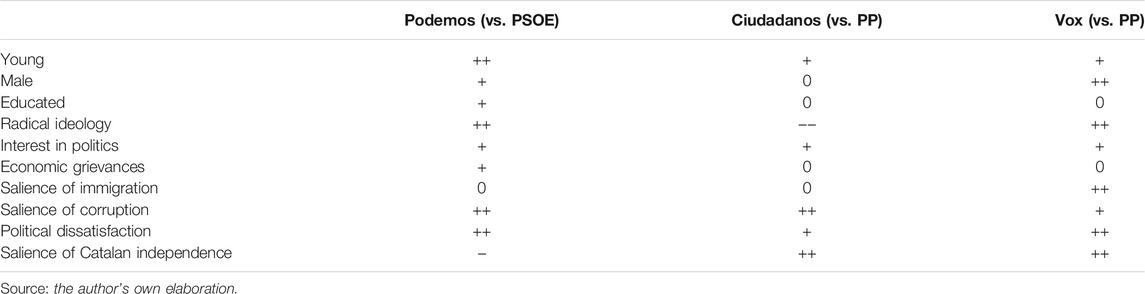

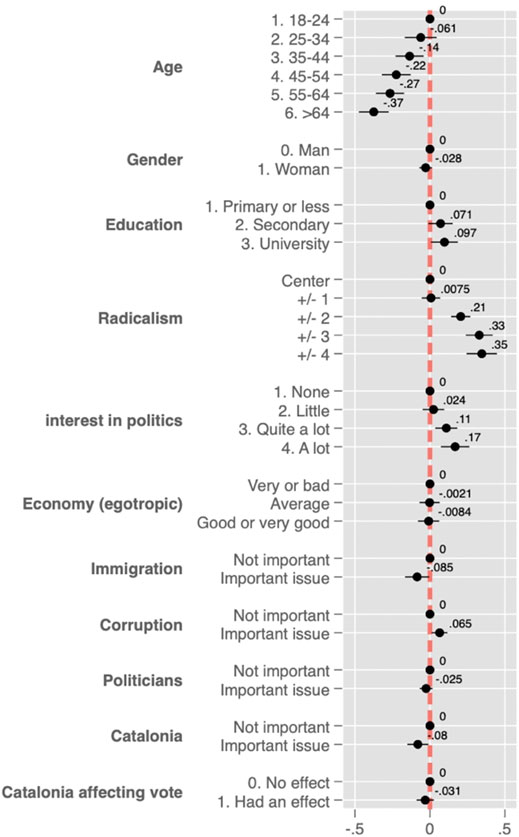

Figure 7 displays the average marginal effects (AMEs) of the independent variables on voting for Unidas Podemos against voting for PSOE. Figure 8 displays AMEs of the same independent variables on voting for Ciudadanos over PP (left panel) and Vox over PP (right panel). Supplementary Appendix S2 for the logistic regression coefficients of models ran before estimating the AMEs. In this sense, the AMEs are calculated as follows: for each observation in the dataset, the marginal effect of a given variable (holding all other independent variables constant) on the dependent variable is estimated and then averaged for all the observations. Each horizontal line in Figures 7, 8 represents a category of an independent variable (the first category is always the reference one), with the dot being the best estimation of its effect upon the dependent variable and the line the 95% confidence interval. If a confidence interval crosses the red vertical line of null effect, the effect of the variable is not statistically significant. If it does not and is located to the right, the effect is positive and statistically significant, whereas if it is located to its left, the effect is negative and statistically significant.

FIGURE 7. AMEs of voting for Unidas Podemos versus PSOE. Source: Own elaboration based on CIS (2019b).

FIGURE 8. AMEs of voting for Ciudadanos (A) and Vox (B) vs. PP. Source: Own elaboration based on CIS (2019b).

What Figure 7 shows is that, in line with our expectations, supporters of Unidas Podemos differ from voters of the traditional left (PSOE) on several dimensions. First, they are more likely to be younger, university educated (although the latter effect seems small), and interested in politics than PSOE voters. This does not necessarily mean that Unidas Podemos is better at attracting the young than PSOE, but rather that, unlike the socialists, Unidas Podemos lacks support from the middle-aged and older constituencies. Unidas Podemos’ voters also see the issue of corruption as a more salient one (although the effect is substantively small). Not surprisingly, voters of Podemos tend to have a more radical ideology than the supporters of the socialists. However, contrarily to our expectations, gender, economic grievances, and political disaffection (here, “politicians, parties and politics” as one of the main concerns) do not have significant effects. On this regard, the Unidas Podemos’ voter profile seems to have changed since 2015 (Orriols and Cordero, 2016). Immigration seems less salient for supporters of Unidas Podemos (small negative coefficient at 0.1 significance level). Interestingly, although voters of Unidas Podemos are less likely to include the Catalan issue as one of their top concerns, it did not affect their vote choice distinctively from the voters of PSOE.

In contrast, Figure 8A demonstrates supporters of Ciudadanos do not differ much from voters of PP. The only significant differences encountered confirm that they tend to be younger, less radical (with those further from the center being more likely to support PP), and more likely to list corruption as one of the key concerns. The Catalan issue of such importance for the emergence of Ciudadanos no longer distinguishes their voters significantly from the supporters of PP neither in salience nor in direct effect on vote choice.

The supporters of Vox, on the other hand, do differ to a greater extent from voters of PP, as Figure 8B shows. In line with the hypothesized effects, Vox’s supporters are more likely to be younger, males, and have radical ideology. Supporters of Vox also tend to be more concerned with immigration but not as much with corruption (the latter effect is small and significant only at the level of 0.1). Contrarily to our expectations, they are more likely to express economic grievances compared to voters of PP but not to be more politically dissatisfied nor interested in politics. Additionally, our findings show that they tend to have secondary education levels. Regarding the issue of Catalan independence, the results show that despite the nonsignificant difference in this issue salience between supporters of Vox and PP, the former tend to admit with higher frequency that it was an important issue for their vote choice (56% admit that compared to 25% of all voters and 35% of supporters of PP—Figure 6). Thus, the impact on vote choice of the Catalan issue significantly distinguishes supports of Vox from PP’s voters.

Taken together, the insights from the point of view of the differences between the voter bases of new versus old parties show, in the first place, that while Unidas Podemos and Vox are more likely to succeed in establishing linkages with groups of voters significantly distinct from supporters of PSOE and PP, Ciudadanos’ base of support is not that different from voters of the traditional right. Hence, as recent poor electoral results of Ciudadanos confirm, this party seems to be heading towards sharing the fate of UPyD and disappearing. Recent explosive developments at the regional level with Ciudadanos supporting unsuccessful motions of no confidence to its own governments shared with the PP in Murcia, or the call for new elections by Isabel Díaz Ayuso, the President of the Comunidad de Madrid (from the PP), basing her decision on the worry that Ciudadanos, would present a censure motion in Madrid (Ciudadanos was the minor coalition partner with the PP) demonstrating that this party is trying to reinvent itself once again fearful of disappearing. However, the recent regional elections of Madrid Community, held in May 2021, confirm the implosion of Ciudadanos, who fell from 26 to 0 seats in Madrid’s regional parliament.

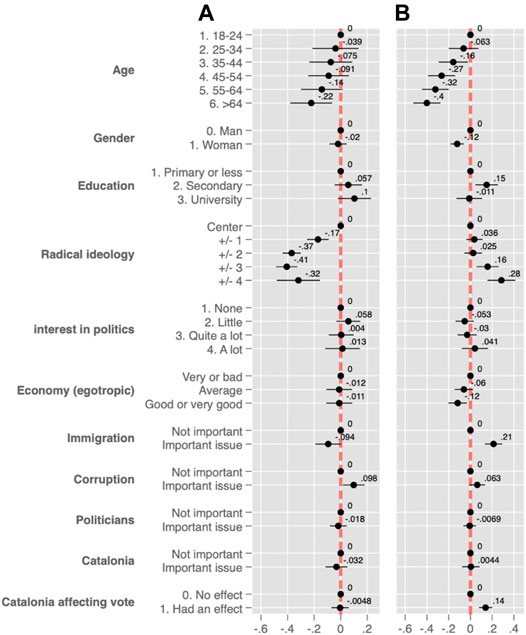

Secondly, although plenty of our expectations based on the existing literature found empirical support (e.g., age and corruption), we also encountered some important inconsistencies. Perhaps the most intriguing one is related to political dissatisfaction. Unlike we anticipated, voters of the new parties are not more likely to deem politicians to be one of the most important concerns for the country compared to voters of the traditional mainstream parties. One explanation for this fact is that most citizens in Spain are concerned with the politicians, independently of their political preferences. The data confirm that up to some point—54% of supporters of PP, 53% of Vox, 52% of Ciudadanos, 47% of PSOE, and 46% of Podemos list “politicians, parties, and politics” as one of the three main problems Spain faces. What is more relevant, however, is that while political dissatisfaction might be a driving factor of the vote for new parties that are outsiders to the system, as it is harder for voters to consider their newly-elected representatives to be a problem, supporters of Podemos, Ciudadanos, and Vox insiders, sometimes even sharing governmental responsibilities in 2019, are not more politically unsatisfied than the ones of PP or PSOE anymore. Once new parties lose their outsider’s flair, part of those characteristics that might have proven crucial for these parties’ entrance (i.e., economic grievances in the case of Unidas Podemos and political dissatisfaction for all) seem to not distinguish their supporters from the voters of more established political parties anymore. All in all, Table 2 summarizes the extent to which our hypothesized effects are (or not) empirically confirmed (with confirmed effects in bold).

TABLE 2. Summary of the results of effects of individual level factors for voting for Podemos vs. PSOE, Ciudadanos vs. PP, and Vox vs. PP.

Discussion

The Spanish party system has been characterized since the early 80s by its great stability. The two major parties, PP and PSOE, have been able to alternate in power without major changes in the supply of parties for more than 30 years. However, the emergence of three new options as of 2015 has meant the end of (imperfect) bipartisanship in Spain. In this article, we discussed how the traditional sets of explanations of new parties’ entries— institutional, sociological, and economic—fit this recent radical change in the Spanish party system. Until recently, the Spanish party system was characterized by its evolution towards a two-plus party system and by being the European exception for not having far-right parties in the National Parliament. However, the irruption of the left-wing populism (Podemos), center-liberalism (Ciudadanos), and the populist radical right (Vox) has meant a profound reshaping of the country’s political landscape. If the party system in Spain was so stable, what has made such a radical change possible in such a short time? In this article we tried to answer this question from the supply side-shedding light on the institutional setting and political opportunity structures that allowed for the recent emergence of new parties in Spain. From the demand-side, we analyze the voter profile of these new parties to check if the reasons behind vote switching from the established parties to the newly emerged ones remain valid after their breakthrough.

By using institutional explanations, we defended that Ciudadanos, Podemos, and Vox made their debut in second-order elections, in which electoral systems are more permissive than in the national elections in Spain and voting dynamics are more favorable for smaller parties, allowing also newly created parties to be perceived by the electorate as more viable when it comes to general elections. Thus, while Podemos gathered convincing result already in this contest, the first resounding success of Ciudadanos was in the Catalan regional elections held in 2015 and that of Vox in the Andalusian elections of 2018 (12 out of 109 seats), all second-order ones with a proportional electoral system.

However, as previous literature has pointed out that the proportionality of the electoral system is only the facilitator of the success of new parties. For a party to be successful in its emergence, two other circumstances must exist. The first one has to do with the economy. Despite the fact that for more than 30 years the Spanish bipartisan system has been able to respond to the different economic crises, the Great Recession and its social and political consequences are behind the first success of Podemos. Social discontent and public distrust in traditional parties explain the emergence of a new left-wing populist party critical of the political class and openly against the social cuts as a result of the crisis. Although undoubtedly the context of economic and social crisis facilitates it, the electoral success of Ciudadanos and Vox has, however, a more sociopolitical than economic root. Both parties have as their raison d’être the criticism of widespread corruption in the PP and the secessionist crisis in Catalonia. Both parties presented themselves as the solution to party corruption and showed tough stances against secessionism in Catalonia. These speeches soon found electoral support at a time of great political discontent.

From the political demand side, according to our analyses, voters of all new parties under scrutiny are characterized by being younger and more concerned about corruption than voters from traditional parties. Moreover, Podemos’ voters tend to have higher levels of education, a more extreme ideology and greater interest in politics than the PSOE voters. For her part, the Ciudadanos voter differs from the PP voter in having more centric ideological stances. The Vox voter, however, does show clear differences with the traditional PP voter. Not only is he more likely to be younger, more masculinized, and medium-educated, but he also tends to be more ideologically radical, concerned about immigration admitting that the issue of Catalonia determined his vote.

The significant expansion of the supply both on the left and on the right leads us to wonder about the viability of this wide partisan offer in the medium term. This greater differentiation of Vox and Podemos with respect to their natural competitors (PP and PSOE) should facilitate the survival of these new parties. Although Podemos is currently a partner in the PSOE government and is in process of changing the leadership, its support shows certain stability in the polls. While Vox seems to be on the rise, placing itself as the third biggest player at the national level, the future of Ciudadanos appears to be in danger. The inability of Ciudadanos to be an alternative government in Catalonia and depolarize the debate on secessionism, the sustained support for parties with significant corruption problems and the party’s shift to the right fruitful in the short-term could be among the reasons for the electoral fall of Ciudadanos.

In any case, as we argued in the article, the current distribution of votes among the party supply depends much on the saliency of corruption, immigration, and secessionism, issues that have shaped and will continue shaping the ideological and nationalist axes of competition in Spain. In the highly polarized context of Spanish politics, it is the extreme options of Vox and Podemos that have the highest chances of becoming the first success stories of new parties at the national level in the recent history of Spain. Although Ciudadanos is recently trying to solve its precarious situation with a rapprochement with PSOE, its future does not seem guaranteed in the medium term.

So, if the question is: “three is a crowd?”, the answer is no. The recent political earthquakes (2015 and 2019) that have shaken Spanish politics have altered many of its well-established dimensions, such as party fragmentation or electoral volatility, but have been still unable to profoundly change other well-rooted elements such as the relevance of major cleavages that structure the party competition (Rodríguez-Teruel et al., 2019). Thus, despite new political opponents (Podemos, Ciudadanos, and Vox) have tried to steal and attract the voters of traditional forces (PSOE and PP) with the politicization of new issues (such as democratic regeneration, territorial reorganization, feminism, or anti-immigration politics), the truth is that 1) at the subnational level, all of the 17 Spanish autonomous communities keep being ruled by traditional forces and 2) the Spanish political competition continues as a left-right game where the ideological and territorial dimensions are the main elements structuring the vote choice.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: http://www.cis.es/cis/opencm/ES/1_encuestas/estudios/ver.jsp?estudio=14479.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2021.688130/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1We measure electoral volatility with the Pedersen (1979): 6 index which captures “the net change within the electoral party system resulting from individual vote transfers”. The formula is the following: Total Electoral Volatility = ½ Σ|vi,t–vi,t-1|, where vi,t is the vote share of party i at election t preceded by election t-1.

2In 2016, IU fused with Podemos as Unidos Podemos. In the 2019 November general elections, the party changed its name for the third time from Unidos Podemos to Unidas Podemos as an acknowledgment to the Feminist Movement.

3We calculate the Effective Number of Parties (ENEP), with the following formula: ENEP = 1/Σvi2, where vi is the vote share of party i.

4We thank Professor Ignacio Lago’s contribution to the drafting of this subsection on the PP’s cases of corruption.

5It could be argued that Ciudadanos, being a liberal center party, also gained support from the ex-PSOE voters. Nevertheless, as the major influx of voters came from the PP (Teruel and Barrio, 2016), we focus on this comparison.

6Unfortunately, the CIS 2019 data do not include questions about the direct effects of the other issues on vote choice.

References

Águeda, P. (2014). Anticorrupción investiga el gasto de 15 millones con tarjetas en “negro” de la cúpula de Caja Madrid’. Eldiario.es. Available at: http://www.eldiario.es/politica/Anticorrupcion-investiga-tarjetas-Caja- Madrid_0_309019381.html. October 1.

Alonso, S., and Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2015). Spain: No Country for the Populist Radical Right? South Eur. Soc. Polit. 20 (1), 21–45. doi:10.1080/13608746.2014.985448

Armingeon, K., and Guthmann, K. (2013). Democracy in Crisis? the Declining Support for National Democracy in European Countries, 2007-2011. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 53 (3), 423–442. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12046

Bellucci, P. (2014). The Political Consequences of Blame Attribution for the Economic Crisis in the 2013 Italian National Election. J. Elections, Public Opin. Parties 24 (2), 243–263. doi:10.1080/17457289.2014.887720

Benito, C. (2017). La Generalitat detalla las lesiones de los 1.066 heridos por las cargas policiales del 1-O'. Eldiario.es, Available at: https://www.eldiario.es/catalunya/salut-presenta-informe-detallado-policiales_1_3121320.html. October 20.

Bolin, Niklas. (2007). ‘New Party Entrance – Analyzing the Impact of Political Institutions’. Umea Working Pap. Polit. Sci. 2. 1–20.. Available at: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:562465/FULLTEXT01.%20pdf.

Bosch, A., and Durán, I. M. (2019). How Does Economic Crisis Impel Emerging Parties on the Road to Elections? the Case of the Spanish Podemos and Ciudadanos. Party Polit. 25 (2), 257–267. doi:10.1177/1354068817710223

Casal Bértoa, F., and Enyedi, Z. (2016). Party System Closure and Openness. Party Polit. 22 (3), 265–277. doi:10.1177/1354068814549340

Casal Bértoa, F., and Weber, T. (2019). Restrained Change: Party Systems in Times of Economic Crisis. J. Polit. 81 (1), 233–245. doi:10.1086/700202

Casals, X. (2020). El Ultranacionalismo de VOX. Cinco claves para comprender "La España viva", Grand Place. Pensamiento y Cultura 13 (2), 27–35.

CIS (2019a). Estudio 3248. Postelectoral Elecciones Generales Abril (April) 2019. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS). Available at: http://www.cis.es/cis/opencm/ES/1_encuestas/estudios/ver.jsp?estudio=14453 (Accessed March 2021).

CIS (2019b). Estudio 3269. Postelectoral Elecciones Generales Noviembre (November) 2019. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS). Available at: http://www.cis.es/cis/opencm/ES/1_encuestas/estudios/ver.jsp?estudio=14479. (Accessed March 2021).

Cordero, G., and Blais, A. (2017). Is a Corrupt Government Totally Unacceptable? West Eur. Polit. 40 (4), 645–662. doi:10.1080/01402382.2017.1280746

Cordero, G., and Christmann, P. (2018). “Podemos. Crónica de un éxito inesperado,” in Crisis Económica e Institucional y Ciudadanía en España. Editor M. Torcal (Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas).

Cordero, G., and Montero, J. R. (2015). Against Bipartyism, towards Dealignment? the 2014 European Election in Spain. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 20 (3), 357–379. doi:10.1080/13608746.2015.1053679

Cordero, G., and Simón, P. (2015). Economic Crisis and Support for Democracy in Europe. West Eur. Polit. 39 (2), 305–325. doi:10.1080/01402382.2015.1075767

Dassonneville, R. (2013). Questioning Generational Replacement. An Age, Period and Cohort Analysis of Electoral Volatility in the Netherlands, 1971-2010. Elect. Stud. 32 (1), 37–47. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2012.09.004

Dinas, E., and Riera, P. (2018). Do European Parliament Elections Impact National Party System Fragmentation? Comp. Polit. Stud. 51 (4), 447–476. doi:10.1177/0010414017710259

Farrer, B. (2015). Connecting Niche Party Vote Change in First- and Second-Order Elections. J. Elections, Public Opin. Parties 25 (4), 482–503. doi:10.1080/17457289.2015.1063496

Fernández-Villaverde, J., Garicano, L., and Santos, T. (2013). Political Credit Cycles: The Case of the Eurozone. J. Econ. Perspect. 27 (3), 145–166. doi:10.1257/jep.27.3.145

Ford, R., and Jennings, W. (2020). The Changing Cleavage Politics of Western Europe. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 23 (1), 295–314. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-052217-104957

Fortes, B. G., and Urquizu, I. (2015). Political Corruption and the End of Two-Party System after the May 2015 Spanish Regional Elections. Reg. Fed. Stud. 25 (4), 379–389. doi:10.1080/13597566.2015.1083013

Fraile, M., and Lewis-Beck, M. S. (2012). Economic and Elections in Spain (1982-2008): Cross-Measures, Cross-Time. Elect. Stud. 31 (3), 485–490. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2012.02.012

Gougou, F., and Persico, S. (2017). A New Party System in the Making? the 2017 French Presidential Election. Fr Polit. 15, 303–321. doi:10.1057/s41253-017-0044-7

Green-Pedersen, Ch. (2010). New Issues, New Cleavages, and New Parties: How to Understand Change in West European Party Competition. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1666096.

Guntermann, E., Blais, A., Lago, I., and Guinjoan, M. (2018). A Study of Voting Behaviour in an Exceptional Context: the 2017 Catalan Election Study. Eur. Polit. Sci. 19, 288–301. doi:10.1057/s41304-018-0173-8

Harmel, R., and Robertson, J. D. (1985). Formation and Success of New Parties. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 6, 501–523. October. doi:10.1177/019251218500600408

Haughton, T., and Deegan-Krause, K. (2020). The New Party Challenge: Changing Patterns of Party Birth and Death in Central Europe and beyond. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198812920.001.0001

Hauss, C., and Rayside, D. (1978). “The Development of New Parties in Western Democracies since 1945,” in Political Parties: Development and Decay. Editors L. S. Maisel, and J. Cooper (Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE).

Hino, A. (2012). New Challenger Parties in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203130698

Hooghe, L., and Marks, G. (2018). Cleavage Theory Meets Europe's Crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the Transnational Cleavage. J. Eur. Public Pol. 25 (1), 109–135. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1310279

Huffington Post (2014). Los nombres de los consejeros de Caja Madrid: quiénes fueron y cuánto gastaron presuntamente con tarjetas B. Huffington Post, Available at: http://www.elespanol.com/espana/20151201/83491652_0.html October 2.

S. Hutter, and H. Kriesi (Editors) (2019). in European Party Politics in Times of Crisis. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Klüver, H., and Spoon, J.-J. (2020). Helping or Hurting? How Governing as a Junior Coalition Partner Influences Electoral Outcomes. J. Polit. 82 (4), 1231–1242. doi:10.1086/708239

Kotroyannos, D., Tzagkarakis, S. I., and Pappas, I. (2018). South European Populism as a Consequence of the Multidimensional Crisis? the Cases of SYRIZA, PODEMOS and M5S. Eur. Q. Polit. Attitudes Mentalities 7 (4), 1–18.

Laakso, M., and Taagepera, R. (1979). "Effective" Number of Parties. Comp. Polit. Stud. 12 (1), 3–27. doi:10.1177/001041407901200101

Lago, I. (2021). Electoral Rules and New Parties: Evidence from a Quasi‐experimental Design. Front. Polit. Sci. 3, 623709. doi:10.3389/fpos.2021.623709

Lago, I., and Martínez, F. (2011). Why New Parties?. Party Polit. 17 (1), 3–20. doi:10.1177/1354068809346077

Linz, J. J., and Montero, J. R. (2001). “The Party Systems of Spain: Old Cleavages and New Challenges,” in Party Systems and Voter Alignments Revisited. Editors L. Karvonen, and S. Kuhnle (London: Routledge), 150–196.

Llera, J., Baras, M., and Montabes, J. (2018). Las elecciones Generales de 2015 y 2016. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS).

M. Lisi (Editors) (2019). “Party System Change,” in The European Crisis and the State of Democracy. Abingdon, England: Routledge.

Magalhães, P. C. (2014). The Elections of the Great Recession in Portugal: Performance Voting under a Blurred Responsibility for the Economy. J. Elections, Public Opin. Parties 24 (2), 180–202. doi:10.1080/17457289.2013.874352

Mainwaring, S., and Torcal, M. (2006). “Party System Institutionalization and Party System Theory after the Third Wave of Democratization,” in Handbook of Political Parties. Editors R. S. Katz, and W. Crotty (London: Sage), 204–227.

Manetto, F., and Cué, C. E. (2013). ‘Rajoy Niega Los Ingresos Y Descarta Dimitir’. El País. Available at: http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2013/02/02/actualidad/1359804393_777742.html. February 3.

Marcos-Marne, H., Plaza-Colodro, C., and Freyburg, T. (2020). Who Votes for New Parties? Economic Voting, Political Ideology and Populist Attitudes. West Eur. Polit. 43 (1), 1–21. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1608752

Martí, D., and Cetrà, D. (2016). The 2015 Catalan Election: Ade Factoreferendum on independence? Reg. Fed. Stud. 26 (1), 107–119. doi:10.1080/13597566.2016.1145116

Martín, I., Paradés, M., and Zagórski, P. (2021). How the Past Influences the Vote of the Populist Radical Right Parties in Germany, Poland and Spain. unpublished manuscript.

Mendes, M. S., and Dennison, J. (2021). Explaining the Emergence of the Radical Right in Spain and Portugal: Salience, Stigma and Supply. West Eur. Polit. 44 (4), 752–775. doi:10.1080/01402382.2020.1777504

Méndez, M. (2020). “Parties and Party System,” in The Oxford Handbook of Spanish Politics. Editors D. Muro, and I. Lago (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 331–348.

Minder, R. (2014). Former Bankia Chairman Rodrigo Rato Is Accused of Misusing Company Credit Cards. The New York Times. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/09/business/international/former-bankia- chairman-rodrigo-rato-is-accused-of-misusing-company-credit-cards.html. October 8.

Montero, J. R. (1988). Elecciones y ciclos electorales en España. Revista de Derecho Político 25, 9–34.

Montero, J. R., and Lago, I. (2010). Elecciones Generales 2008. Madrid, Spain. Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS).

Montero, J. R., and Santana, A. (2020). “Elections in Spain,” in The Oxford Handbook Of Spanish Politics. Editors D. Muro, and I. Lago (Oxford Handbooks New York: Oxford University Press), 347–369.

Morlino, L., and Raniolo, F. (2017). The Impact of the Economic Crisis on South European Democracies. Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/979-3-319-52371-2

N. Lagares, C. Ortega, and P. Oñate (Editors) (2019) Las elecciones autonómicas de 2015 y 2016 (Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas).

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108595841

Orriols, L., and Cordero, G. (2016). The Breakdown of the Spanish Two-Party System: The Upsurge of Podemos and Ciudadanos in the 2015 General Election. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 21 (4), 469–492. doi:10.1080/13608746.2016.1198454

Orriols, L., and Rodon, T. (2016). The 2015 Catalan Election: The Independence Bid at the Polls. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 21 (3), 359–381. doi:10.1080/13608746.2016.1191182

Pardo, I. (2013). Los juzgados valencianos investigan 141 casos de corrupción de políticos en activo. Cadena Ser. Available at: https://cadenaser.com/emisora/2013/04/10/radio_valencia/1365551445_850215.html.

Pedersen, M. N. (1979). The Dynamics of European Party Systems: Changing Patterns of Electoral Volatility. Eur. J. Polit. Res 7 (1), 1–26. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.1979.tb01267.x

Pérez Nievas, S., and Rama, J. (2018). Las bases sociales y actitudinales del nacionalismo: Cataluña, Galicia y País Vasco en Agustín Blanco Martín (Coord.) Informe España 2018 Cátedra Martín Patino. Madrid, Spain: Universidad de Comillas, 301–359.

Pinard, M. (1971). “Rise of a Third Party: A Study in Crisis Politics,”. Palgrave in Grievances and Public Protests: Political Mobilisation in Spain in the Age of Austerity (Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall General.Portos, M).

Rama, J., and Martín, I. (2019). “La Comunidad de Madrid: la anticipación de una nueva dimensión de competición,” in En busca del poder territorial: cuatro décadas de elecciones autonómicas en España. Editors B. Gómez, S. Alonso, and L. Cabeza (Madrid: Serie Academia Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas), 42, 347–369.

Rama, J., Zanotti, L., Turnbull-Dugarte, S. J., and Santana, A. (2021). Vox. The Rise of the Spanish Populist Radical Right. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003049227

Ramiro, L., and Gomez, R. (2017). Radical-Left Populism during the Great Recession: Podemos and its Competition with the Established Radical Left. Polit. Stud. 65 (1_Suppl. l), 108–126. doi:10.1177/0032321716647400

Reif, K., and Schmitt, H. (1980). Nine Second-Order National Elections - a Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of European Election Results. Eur. J. Polit. Res 8 (1), 3–44. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.1980.tb00737.x

Ribera Payá, P., and Martínez, J. I. D. (2020). The End of the Spanish Exception: the Far Right in the Spanish Parliament. Eur. Polit. Soc. 22, 410–434. doi:10.1080/23745118.2020.1793513